Growing up in New York, Norwood’s father gave her a gift when she was 9 years old: a slide rule. The girl was interested in math, and that helped develop her skills. Her father was an army officer and physicist, and her mother studied math and languages. It was a rich learning environment, yet her high school guidance counselor suggested Virginia might want to be a librarian. You know, because she was a girl. Instead, she applied at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, which not only accepted her application, it gave her a scholarship. She graduated MIT with a degree in mathematical physics, a few semesters of graduate-level courses, and a new husband: Larry Norwood was one of her calculus instructors, and was president of MIT’s math club.

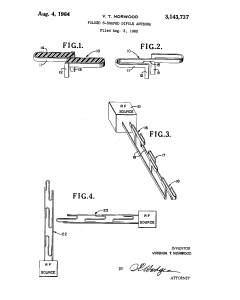

After a number of false starts (when asked to promise not to get pregnant if hired at a food lab, Norwood withdrew her application), she and her husband were finally snapped up by the U.S. Army Signal Corps, and she continued to study math at Rutgers University. “The government labs could not discriminate against women,” she noted. “They were obliged to take on all comers. As a result, we [also] had many more professionals who were Black than I ever saw subsequently.” Her job at the Signal Corps: improving weather radar systems, for which she designed a radar reflector for weather balloons so that high-altitude winds — above 100,000 ft. — could be measured. “This feat,” MIT said in 2021, “made long-term weather prediction possible for the first time.” Norwood was just 22 years old, and her name is on the resulting patent. With that tackled, she was moved into a new field: microwave antenna design.

After five years Norwood was hired away by Hughes Aircraft Co. in southern California, where she was the only woman among the 2,700-strong staff at its R&D labs. She worked there for 36 years on antenna design, communications links, optics, and an instrument for Landsat satellites. “We built some very interesting antennas,” she said in 2021, “some of which I can tell you about.” One thing she worked on that is now declassified: she designed the antenna for an improved IFF system on military aircraft — Identify Friend or Foe. Her name is on that patent too. “I guess it worked,” she winked. When she was put in charge of microwave antenna research, one engineer quit because he didn’t want to work for a woman — or a company “stupid enough” to put a woman over him. Norwood shrugged — and went back to work, designing the microwave transmitter that the first soft-landing probe to the moon, Surveyor 1, used to transmit data and images back to Earth. The man who quit came crawling back — and Norwood didn’t hire him. She was promoted to Hughes’ Space Systems Division.

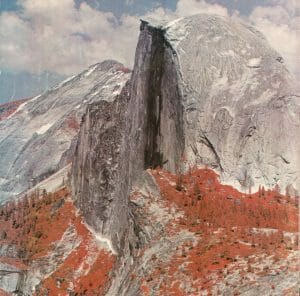

But mostly she worked on the scientific payload for a program called the Earth Resources Technology Satellite, later named Landsat, a series of satellites built for NASA and the U.S. Geographic Survey which have been looking back at Earth since 1972. She had been watching what NASA was doing, and came up with the idea for a special instrument for it herself, and then did the research to make it happen. But first she had to get the funding. “I went to [Hughes Aircraft CEO Allen] Puckett and I said, ‘I need $100,000 in order to build a breadboard [prototype],’ and he gave it to me. My management didn’t understand all that I was doing.” Her first prototype was completed within nine months, and was tested by scanning Half Dome at Yosemite National Park. Her spectrometers flew starting with Landsat 1. For this design work, Norwood is considered by NASA “The Mother of Landsat.” MIT calls her “The woman who brought us the world.” The latest in the series, Landsat 9, was launched in 2021; Norwood was invited to see it take to the sky from Vandenberg Space Force Base. “She paved the way for an entire generation of … Earth observation instruments,” said Landsat project scientist Jeffrey Masek of NASA.

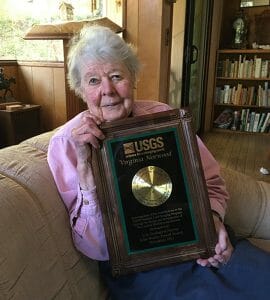

Norwood received the Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing in 2021 for her far-reaching impact on the field of remote sensing. In 2021, the U.S. Geological Survey awarded her the John Wesley Powell Award in recognition of her work on Landsat, which has “transformed our understanding of regional, national and global-scale agriculture, forestry, urbanization, hydrology, disaster mitigation and other changes in land use.” In 2022 she received the American Geographical Society’s O.M. Miller Cartographic Medal for her development of the MSS, which “transformed expectations of how we can know the Earth.” And in February, she was elected to the National Academy of Engineering, which is reserved for those who have made outstanding, novel contributions to the field of engineering — among the highest professional distinctions possible for an engineer. Norwood retired from Hughes in 1989. Along the way she had children, taking off — at most — three days from work.

When asked in 2021 what it was like to see so many women in science coming in behind her, Norwood said, “I’ve spent my life where I was the only woman in a program. Now, there’s a whole group of them. That’s kind of nice.” Her most important lesson was as a pioneering woman in science? “Not to accept other people’s negativity. If somebody says, ‘You can’t do it,’ I sort of prick up my ears and decide that I’ll do it.” For her, “it was all fun. And when something is fun, you just keep at it.” Virginia Tower Norwood died on March 26. She was 96.