Growing up in Illinois, Kurtz was interested in science, and once he entered college he fell in love with math, taking every course offered at Knox College, graduating there in 1950. During a summer session at UCLA in 1951, he was introduced to a computer, and earned his Ph.D at Princeton in 1956. He was recruited almost immediately to teach at Dartmouth College by John G. Kemeny, who went on to become the President of Dartmouth. Kurtz taught statistics and numerical analysis. Kemeny helped Dartmouth to get its first computer in around 1961, and it was a project meant to help students that Kurtz and Kemeny are best known for: they jointly led the development of a new computer programming language designed to be easy to understand. Their students did a lot of the work.

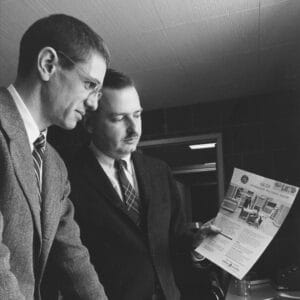

At the time, each model of computer essentially needed to be programmed in its own “low level” assembly language, and various computer scientists were working on “higher level” languages that could be used on multiple models. In addition, computers tended to work on one job at a time, often fed in using a stack of punched cards. Kurtz and Kemeny not only wanted to create a high-level language, but also create a way for multiple people to work with a computer at the same time. So while the language was being developed, Kurtz and Kemeny also created an operating system, Dartmouth Time-Sharing System (DTSS), on which the higher level language would run, and accommodate multiple users at once, with each user getting a brief “share” of computer time in sequence, but fast enough that delays were tolerable. Kurtz called the programming language BASIC, for “Beginner’s All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code”.

As DTSS and BASIC were coming together in 1963, Kemeny got a grant from the National Science Foundation to buy a General Electric 235 computer for Dartmouth, which GE set up to run the software. The idea was revolutionary. “The target [in computing] was research,” Kurtz explained later, “whereas here at Dartmouth we had the crazy idea that our undergraduate students who are not going to be technically employed later on should learn how to use the computer. Completely nutty idea.” And it took off. “I once estimated that even before Bill Gates got into the action at all, five million people in the world knew how to write programs in BASIC,” Kurtz said in an oral history for Dartmouth in 2020. “There was something like 80 time-sharing systems in the U.S. that offered BASIC as one of their languages. And it was all over the world. I even got a letter from somebody in Siberia.”

While many future coders looked down on BASIC as a “toy” language created for “educational” purposes, it made it possible for non-math geeks to program computers for the first time, including me as a junior-highschooler in 1972. The DTSS/BASIC package had been adopted by multiple computer manufacturers as an easy way to get their systems up and running in a productive way very quickly, and was a key component when the first hobbyist microcomputer, the Altair 8800, hit the market in 1974. (That version of BASIC was written in 1978 by two Harvard students, Paul Allen and Bill Gates, who called their company Micro-Soft.)

Having computers easier to access (because of time sharing) and easier to program (because of BASIC) meant that computers were much more available to non-scientists and computer nerds. “Dartmouth had the largest open-stack library in the world at that time in a college of this type, and the concept of open-stack computing, that was my idea,” Kurtz once said. “That’s one of the few ideas I had that Kemeny didn’t have.” He made computers more available to everyone, which meant more computers were built, such as the low-cost Altair, meaning more people could use them, meaning more computers were needed until pretty much everyone has access to one.

In 1979, Kurtz, with Dartmouth’s Stephen Garland, created a Master’s degree program for the school in Computer and Information Systems — the first of its kind, according to Dartmouth. In 1991, the IEEE honored Dr. Kurtz with the Computer Pioneer Award for his role in creating BASIC. He retired in 1993. “Tom’s groundbreaking work — and enlisting of undergraduates to execute his and John Kemeny’s vision — played a major role in making computers accessible to the general public, and proved that students, not specialized engineers, could drive this new movement,” said Elizabeth F. Smith, Darthmouth’s dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences. Thomas Eugene Kurtz died in hospice in Lebanon, N.H., on November 12. He was 96.