Born in Brussels, Belgium, Sténuit loved to explore caves. By age 20 he was itching to explore flooded caves too, so he learned scuba diving. That in turn led to diving to find shipwrecks, and he quit college — he had intended to become a lawyer. “My father dutifully warned me of the pitfalls” of quitting, he said years later, “and tried to persuade me out of it. But like any good father, he said, ‘If this is what you really want to do, how can I help?’” Despite spending much time looking for the treasures of the Spanish fleet sunk in 1702 at the Battle of Vigo Bay, he failed. Still, he got a job with the American Atlantic Salvage Company, working on a specially equipped ship for an unsuccessful two-year mission to find the 1702 Plate Fleet. In 1999 an interviewer asked him, What was his favorite dive? Sténuit smiled and replied, “The next one, of course!”

After the failed Vigo Bay expedition, Sténuit happened to meet Edwin Link, who was gearing up to do underwater explorations and treasure hunting. Link, who had become rich by inventing the flight simulator (Link is discussed in my 2020 podcast episode, A Link to the Future), was gearing up for a new adventure, which he called the Man-in-Sea Project: building an underwater habitat that could sustain human life. Link had done a test dive in August 1962 using a helium-oxygen mix, and stayed underwater for an astounding 8 hours, but wanted a younger man to try for much longer. Sténuit accepted the challenge, and that September spent over 24 hours in Link’s “submersible decompression chamber” or SDC, at a depth of 200 feet (61 m), and thus became the world’s first aquanaut (“a person who remains underwater, breathing at the ambient pressure for long enough for the concentration of the inert components of the breathing gas dissolved in the body tissues to reach equilibrium, in a state known as saturation.”)

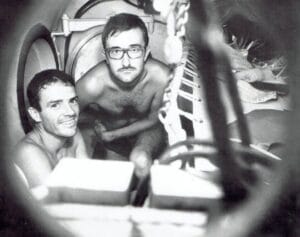

But there was nearly a disaster: the attempt was supported by Link’s yacht, the Sea Diver, but that ship sank during the dive, taking the spare helium tanks with it. The U.S. Navy brought spare helium. Without the support ship, the SDC surfaced. That could have killed Sténuit, but it remained pressurized and, with the new helium supply, could be decompressed slowly enough for him to survive. In June-July 1964, Sténuit and marine biologist/deep sea diver Jon Lindbergh, son of aviator Charles Lindbergh, beat that record, staying 49 hours at a depth of 432 feet in the Bahamas, the recovered Sea Diver again supporting. But… why? “We showed that man can actually live and work in the sea,” he said. The U.S. Navy’s involvement in his rescue on the first dive wasn’t happenstance: it was vitally interested in the project. “It wanted the capability of working in deep water in a military context as well as rescuing lost subs.” The Navy continued the research on their own, with the SEALAB project.

Sténuit and Link then collaborated on another treasure-hunting project, in 1963: trying to find the so-called “Rommel’s Treasure” — gold and jewels looted from North Africa by Heinrich Himmler in World War II. Again, no treasure was found. Link sold the project to Ocean Systems Inc., and Sténuit agreed to stay on as long as they would open an office in London, which he would run. They did, and he did, in 1965. Why? Because after work, Sténuit would go to the British Museum to research the Girona, another sunken Spanish ship, which had gathered treasures from five other Spanish ships — and in 1588 sank before it could get back to Spain. After 600 hours of research, Sténuit was convinced he knew where she lay — miles from where other researchers thought it was. Joined by other divers, he found the Girona on July 27, 1967, finally satisfying his quest. He sought to keep the recovered treasures intact. “If it is in private hands, where will it be after the person dies? Sold off without its background or history or thrown away?” he said. “One can become rich in many ways, but archeology is all about having fun — intellectual fun.” Much of the collection is now in the Ulster Museum in Belfast, N. Ireland. “I asked Ocean Systems for a six-month leave of absence,” he said in 1999, “and I’m still on it.”

His reputation as a serious underwater archeologist set, Sténuit formed the Groupe de Recherche Archéologique Sous-Marin Post-Médiévale (Group for Underwater Post-Medieval Archaeological Research) — GRASP, in both languages — which helped to find wrecks lost during the 16th to 19th centuries. It found 15 vessels. “More expeditions have been made looking for treasure or ships that never existed than for real ones,” Sténuit said. “A day in the library costs a fraction of a day at sea, which can cost $5,000 a day for scuba operations in shallow water to $50,000 a day or more in deep water and with modem technology” — in 1999 dollars. So what’s the real difference between treasure hunters and underwater archeologists? “The treasure hunter spends his own money, or the money of his private backers, instead of the money of the taxpayers,” he said. “This is the only practical way to tell them apart” as they are both driven by the excitement of the find.

Sténuit faded from public view, but his research on diving technology informs scuba systems to this day. He also wrote multiple books (in French), and spent full time operating GRASP with his daughter, archaeologist Marie-Eve Sténuit. “I am not surprised that few people know me,” he said in an interview in 2023. “After all, I do not feel at home in the spotlight and so have put little effort into publicity. If I have any notoriety at all, that is thanks to other people’s efforts.” He died, apparently in Belgium, on December 9. He was 91.