Born in Chicago to a physician father and pianist mother, Barancik served in the U.S. Army during World War II. He was sent to serve with the 232nd Infantry in Austria, where he heard of a special group and immediately applied to join: the Education, Religion, Fine Arts, and Monuments Office in Salzburg. Several such groups coalesced into a team of 345 people from 13 countries called the Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives Section, or MFAA, unit, under the auspices of the Civil Affairs and Military Government Sections of the Allied armies. Their mission: find, repair, and return cultural treasures looted by Nazi Germany. Together, the men and women who served in the unit were dubbed Monuments Men. Barancik was the last one alive.

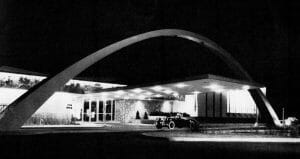

Barancik had no particular education in fine art, but was so inspired by the beauty of Salzberg’s architecture and surroundings that he went into the job with full gusto, helping to repatriate around 5 million pieces of looted art. Once released from the Army, Barancik stayed in Europe to attend a program with the Royal Institute of Architects in London. Now sure of his interests, he studied architecture at the University of Cambridge, and then the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, before he returned home to finish his degree in architecture at the University of Chicago. Richard Conte, one of his design teachers, thought he had great promise as an architect: the two not only went into business together in 1950, but the student’s name came first in the firm’s name: Barancik Conte & Associates. “We struggled for 15 years,” Barancik said. “Our draftsmen made more money than Dick Conte and myself.” But the work, led by Barancik, caught on, bringing dozens of jobs. His building designs, from skyscrapers to bowling alleys, can still be seen throughout Chicago and the surrounding area.

Barancik particularly liked one restaurant: “They have white paper tablecloths that I like because I can draw on them,” he said. After dinner he’d roll up the tablecloth and take it to the office. He would get ideas while eating because “I really practice architecture seven days a week, all my waking hours. It’s an all-consuming profession.” He eventually retired, though, in 1993. He received a resurgence of attention once the 2014 film The Monuments Men * was released. “He’d get fan mail and, once a week, an autograph request,” said his daughter, Jill, who said he previously didn’t talk much about his war experiences. “He’d get sensitive letters from people, lots of them from schoolchildren, which kept the conversation going.”

He still drew, but now it was political cartoons: he had a mailing list of friends who wanted copies. He drew the last one three days before he died. In 2015, there were four Monuments Men still alive, and they went to Washington to receive the Congressional Gold Medal for their “heroic role in the preservation, protection, restitution of monuments, works of art and artifacts of cultural importance.” Barancik told a reporter, “The Americans cared about the cultural traditions of Europe. We did everything we could to salvage what the Nazis had done. It’s the best we could do.” Richard Morton Barancik died in a Chicago hospital on July 14. He was 98.