Born in Iowa, Rene’s mother — who had a job, which was fairly unusual in the 1920s — had divorced when Rene was 2. Her new husband adopted the 8-year-old Rene, which she pronounced “Reen” throughout her life, and the family moved to Boulder, Colorado. After graduating from Boulder High School, she met Scott Carpenter, and they married in Boulder in 1948. Carpenter, about 3 years her senior, had grown up in Boulder, and was friends with a classmate at University Hill Elementary School: Anne Hylan — who later became my mother-in-law (see special photo below). Kit, my wife, remembers the Carpenters; Rene was “a sweet lady,” she said. Scott became a pilot in the U.S. Navy — Rene pinned his aviator wings on him upon his graduation from flight school in April 1951. Scott was a good pilot: his skipper recommended him for the Navy Test Pilot school. He did well there, too: in 1959 he was selected as one of the “Original Seven” U.S. astronauts.

An Expanded Version of this story is published on

Medium: The Last of the Original “Astronaut Wives”.

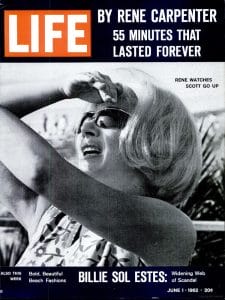

That meant Rene Carpenter was the member of an equally exclusive club: “Astronaut’s Wife” …with all the associated media glare: Life magazine had “exclusive rights” to the “personal stories” of the astronauts and their families, and other outlets competed to get their own photos and stories. The Washington Post described her as a “striking platinum blonde” — and she was. Rene encouraged her husband’s career: when the letter from NASA came telling Scott to report for fitness testing “by Monday,” he was the intelligence officer aboard the USS Hornet (which would later figure in several Apollo missions). Rene opened the letter, called NASA Manpower Director Dr. Allen Gamble, and blurted, “We volunteer!” Gamble held the spot for him. When Scott became the fourth American in space in May 1962, Rene insisted on going to the Cape to watch the launch in person, rather than on TV as wives were encouraged to do. “I don’t care what NASA says,” she said, according to her daughter, Kris Stoever.

Rene also followed in her mother’s footsteps in having an outside job: she was a writer. Her column “A Woman, Still” was syndicated to numerous newspapers starting in 1965 — but not in the Washington Post, even though she was friends with Executive Editor Ben Bradlee. “Ben wouldn’t buy it,” Rene laughed years later. “He said, ‘It’s not good enough.’” She still was allowed to write her own story for Life: “As a bride I was assured by glowing advertisements that I would spend my hours fingering the latest sterling silverware pattern and filling linen closets to overflowing,” she wrote. Instead, “I learned to give birth alone, care for sick babies alone and wait at the end of a hundred almost forgotten runways for a plane to touch down again.”

Like many astronaut couples subjected to the stresses of those early years, in 1972 the Carpenters divorced. She kept her name, even when she later remarried, as she had been using it professionally for years. Rene was invited by Washington Post publisher Kay Graham, who also owned the local CBS-TV affiliate, to develop and host a TV show, Everywoman, which covered “feminist” topics like natural childbirth and sexism. It ran until 1976. “She was keenly alert to everything going on in the space program,” said writer Thomas Mallon, “from its orbital mechanics to its rivalries.” He said that Tom Wolfe got a lot of material from Rene for his book The Right Stuff. Mallon says when he interviewed NASA Flight Operations Director Christopher Kraft Jr. (Honorary Unsubscribe, 21 July 2019), he said he mentioned he was friends with Rene Carpenter. “He lit up with delight and admiration, exclaiming, ‘She should have been picked for the [astronaut] program!’” With the death of astronaut wife Annie Glenn in May, Rene was the last survivor of the Original Seven astronauts and their wives. She died from congestive heart failure in a Denver hospital on July 24, at 92.

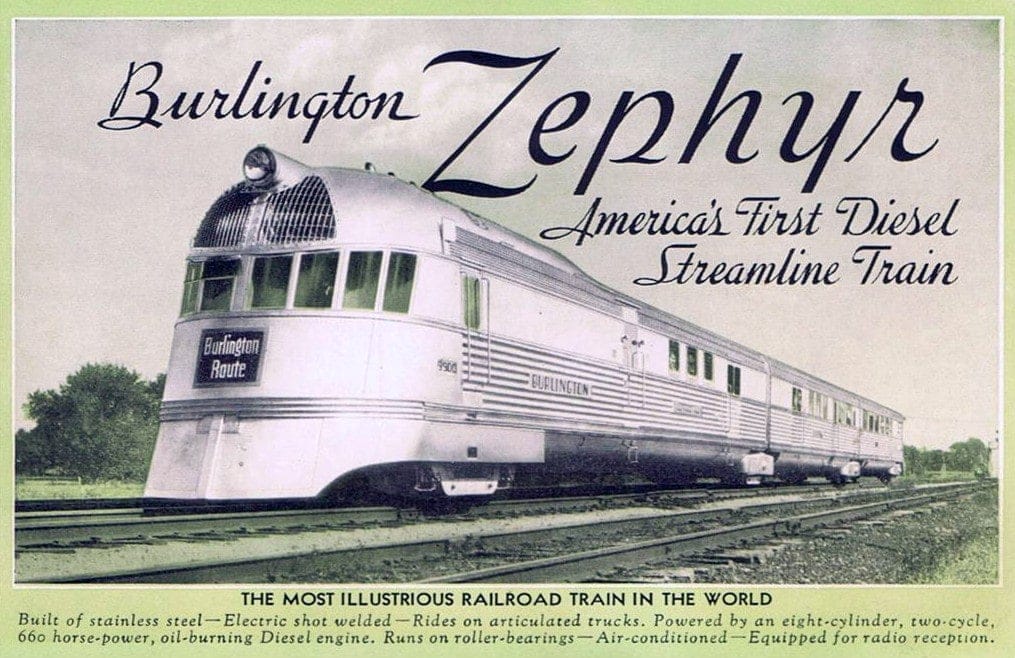

The toy was clearly inspired by this, which perhaps Scott saw in Denver: