To be blunt, Latour was a spy for England during World War II who parachuted into occupied France to relay vital information back to London. For her, it was personal: “I did it for revenge,” she said in a 2009 interview: she had been orphaned at age 4, and in the runup to World War II, her godmother’s father was shot by German soldiers, and her godmother committed suicide after being imprisoned by them. Latour volunteered for the “Special Operations Executive” — more popularly known as Winston Churchill’s “secret army.” She was one of just 39 women in the SOE.

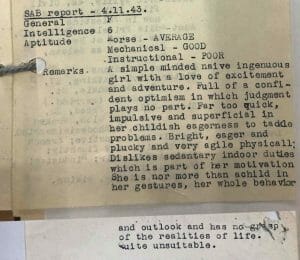

Once she went through rigorous training — “We learned how to get in a high window and down drainpipes, how to climb over roofs without being caught,” she said — her handlers were equally blunt: She was a “simple-minded, naïve, ingenuous girl,” though “bright, eager and plucky,” said one, but then again “childlike” with “no grasp of the realities of life.” Another found her a “cheerfull [sic] little scatterbrain,” as well as “uncontrolled and stubborn,” and “too unreliable emotionally for this type of work.” On the other hand, she handled a gun well.

Clare Mulley, the author of several books about female spies in World War II, points out that male trainers often underestimated female agents. “Latour’s training reports appear dismissive,” she said, “but in France she gave exceptional service.” She parachuted into Normandy on May 1, 1944, sleeping outside when she had to and taken in by allies when she was lucky. Under the codenames Genevieve or Paulette, she called in bombers to specific targets, and for supplies to be dropped for resistance operations.

In one instance, she was sending a report by radio when two German soldiers walked in on her. Latour calmly closed the case, pretending she was packing a suitcase, and told the soldiers that she was leaving since she had been diagnosed with scarlet fever, which was common in the area. The men quickly left. Records show she sent 135 coded messages in just a few weeks. The award citation for her 1945 MBE — Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire — specifically called out her “tons of guts,” and noted she “Wants to go on with the work, provided it’s dangerous enough.”

What had made her so effective as a spy? She was born in South Africa to a French father and a British mother, and when orphaned lived with her uncle in the Belgian Congo. At 16, she was sent to study in Kenya. She spoke English, French, Swahili, Kikuyu (a Bantu language used in Kenya), and some Arabic. After she returned to England she started training for a second mission into Germany, but the Allies had broken through and she was never sent. Released from the SOE, she married an Australian engineer, taking the name Pippa Doyle, and lived in Kenya, Fiji, and Australia before they permanently settled in New Zealand.

In 2014 her story spread more widely, since France made her a Chevalier of the Legion d’Honneur — the highest French order of merit, both military and civil — sending an Ambassador to Auckland to present it. She was surprised that they were able to find her. SOE agents got no support or counseling once they returned from their dangerous missions, Mulley says. “After the thrill of clandestine resistance in enemy-occupied territory, many former SOE agents found it hard to adjust to what one called ‘the horrors of peace’.” Phyllis “Pippa Doyle” Latour died in a New Zealand rest home on October 7 — the last survivor of the 39 female SOE agents. She was 102.