Born Peggy Doris Hawkins in Nashville, Tenn., as a child Peggy lost hearing in one ear during surgery, and learned to understand people better by looking them in the eyes when they spoke. At 10 she started painting. Her subject: children. In the early 1950s she met Walter Keane, who said he was a painter too, and his “suave, gregarious and charming” way lured her away from her husband. She and Keane married in 1955. Walter was taken by his wife’s paintings, which concentrated on the subjects’ eyes: she made “big eyes” paintings popular with her work, and Walter was good at selling them — very good. But unknown to her, he was passing them off as his own work, and he became famous. When Margaret learned of his deception she said nothing: “I was afraid of him because he [threatened] to have me done in if I said anything,” she said later, but tried to balance that with the sales: “At least they were being shown.” Even Andy Warhol liked the style. “I think what Keane has done is just terrific,” he said in the early 1960s. “It has to be good. If it were bad, so many people wouldn’t like it.” By “Keane” he meant Walter.

Furious, Margaret finally had enough, and divorced Walter in 1964. He continued the ruse. “My psyche was scarred in my art student days in Europe, just after World War II, by an ineradicable memory of war-wracked innocents,” he told Life magazine about how “his” paintings were born. “In their eyes lurk all of mankind’s questions and answers. If mankind would look deep into the soul of the very young, he wouldn’t need a road map. I wanted other people to know about those eyes, too. I want my paintings to clobber you in the heart and make you yell, ‘DO SOMETHING!’” He also told the interviewer that “Nobody could paint eyes like El Greco, and nobody can paint eyes like Walter Keane.”

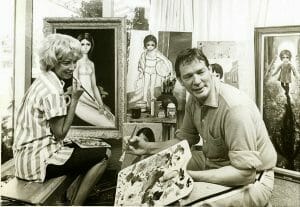

In 1970 Margaret married a man who respected her work, and gave her the courage to come forward. That year she publicly announced that she made all of the “big eyes” paintings that her previous husband claimed were his. She was mostly ignored, in part because Walter continued to claim he was the painter. Margaret challenged Walter to a “paint-off” in San Francisco’s Union Square. He didn’t show up, but a crowd gathered to watch her paint. In 1986 Margaret sued Walter, and the judge thought of a perhaps-obvious way of testing the claim: he ordered Walter and Margaret to appear in his courtroom and paint a “big eyes” portrait under his own watchful eyes. Margaret finished hers in 53 minutes, perfectly matching the style of paintings Walter had sold. Walter, meanwhile, whined that he had a “sore shoulder” and refused to paint for the judge. In fact, other than staged photo opportunities, Walter was never seen painting by anyone. The jury awarded Margaret $4 million. “I really feel that justice has triumphed,” she said. “It’s been worth it, even if I don’t see any of that four million dollars.” She didn’t: a federal appeals court overturned the award, but the verdict that Walter had defamed Margaret by claiming to be her paintings’ creator stood. Margaret kept the Keane name: after all, her work was famous under that name, and the public finally knew the truth about their creation. Walter continued to insist that he was the real artist, even though he couldn’t paint at all. He died in 2000, at 85.

Hollywood actors particularly liked Keane — meaning Margaret: Joan Crawford, Natalie Wood, and Jerry Lewis commissioned her to paint their portraits. Director Tim Burton was a Keane art collector, and released a film about her life with Walter: Big Eyes * (2014). She appeared in a cameo, sitting on a bench outside the Palace of Fine Arts in San Francisco. Without Walter, Keane’s style became brighter, less melancholy. “The eyes I draw on my children are an expression of my own deepest feelings,” she said. “Eyes are windows of the soul.” In 2018 the LA Art Show presented Margaret with its Lifetime Achievement Award. Margaret Keene died at her home in Napa, Calif., on June 26. She was 94.