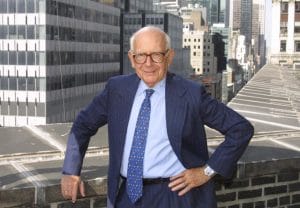

A New Yorker (born in the Bronx), after Wunderman graduated from high school, he decided to take classes from various area colleges and universities to create his own “degree” — learning what he wanted. He took a job in advertising in 1947, and learned the ropes. His big innovation in the early years: placing ads in comic books to reach that demographic. During his time at the agency, where he rose to vice president, he realized that many of the company’s accounts were doing a very poor job at marketing — he thought their ad dollars could go much further with some specific strategies. In 1958 he quit and formed his own agency with his brother and two colleagues, funding it from their own savings. Working out of a Manhattan hotel room, they had no clients, but in their first year sold more than $2 million in bookings.

The opportunity that Wunderman saw: marketing to consumers according to their interests, rather than blanketing consumers with ads hoping that some of them might be interested. Why not intelligently target ads and marketing materials to those who are most likely to buy, which would make the marketing budget much more effective? “‘Direct marketing’ was out there,” he said later. “I didn’t invent it. But it had no definition and no strategy.” He set out to change that: he actually coined the term in 1961, and in a 1967 speech he defined it and set its direction. “A computer can know and remember as much marketing detail about 200 million consumers as did the owner of a crossroads general store about his handful of customers,” he said at the time. “It can know and select such personal details as who prefers strong coffee, imported beans, new fashions and bright colors. Who just bought a home, freezer, camera, automobile. Who had a new baby, is overweight, got married, owns a pet, likes romantic novels, serious reading, listens to Bach or the Beatles.”

Among the innovations that he brought to marketing: the use of toll-free numbers for consumers to order products and services directly. The magazine subscription card. Loyalty reward programs (starting with American Express). And he helped Columbia Records market a mail-order “club” to sell records directly to consumers; it was so successful that the Columbia Record Club had to move its operations to Terre Haute, Indiana — the site of Columbia’s largest record-pressing facility — to streamline operations. President Lyndon Johnson brought Wunderman in to help the postal service market a new mail routing scheme: the “Zone Improvement Plan” — better known as the ZIP Code. In all, Wunderman’s techniques were so successful that in 1973, the giant Young & Rubicam ad agency brought Wunderman’s entire agency under its umbrella as its “direct-marketing subsidiary.” By 1998 it had grown to 65 offices in 39 countries with more than $1.8 billion in yearly billings — about $2.75 billion in today’s dollars. “If there is a lesson to be learned, I believe it is to not do anything half-heartedly,” Wunderman said about his philosophy in life. “If you are going to do it at all, give it all that you have to give.” He died on January 9, at 98.