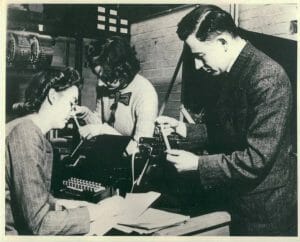

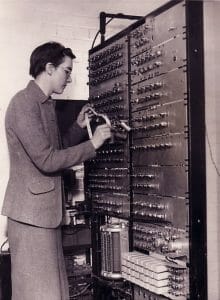

After earning her Bachelor of Science degree in mathematics from the University of London, Britten went on to earn her PhD in Applied Mathematics, and worked with another student at the university’s Birkbeck College, Andrew Booth, to build the country’s earliest computers. After building the Automatic Relay Computer (ARC), with funding from the Rockefeller Foundation they traveled together in the United States for six months, most notably spending time with Princeton computer pioneer John von Neumann. In 1945, von Neumann had led a project to design a digital computer architecture — what became known as the von Neumann Architecture. Britten and Booth returned to the U.K. to build the next version of the ARC, the Simple Electronic Computer, documented in a paper describing the design of this general-purpose stored-program computer based on von Neumann’s ideas, General Considerations in the Design of an All Purpose Electronic Digital Computer. Britten and Booth went on to design more computers — with Booth responsible for the hardware and Britten responsible for the programming.

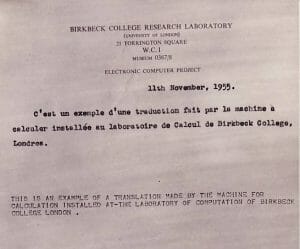

It’s that software where Britten made her mark: she wrote the first assembly language for a general-purpose computer, symbolic machine code that computers can “understand” without interpretation. Assembly language is specific to the computer’s architecture; earlier computers were programmed by physically rewiring them. A stored-program computer is programmed by loading software into memory, most efficiently using assembly language. She went on to write one of the earliest textbooks in the field, Programming for an Automatic Digital Calculator. The couple married in 1950 when they secured funding, again from the Rockefeller Foundation, for their next computer, the All Purpose Electronic X-Ray Computer or APE(X)C; the X could be changed for other purposes for companies that needed specific jobs done. The Foundation had specified they wanted to see a computer do translation of natural language; that was accomplished in 1955. “Braille transcription,” Andrew noted in 2008, “now touted as a recent IBM invention, was actually the work of one of our Ph.D. students” long before. Andrew allowed the British Tabulating Machine Co. to copy the APE(X)C design, which was updated and sold as the Hollerith Electronic Computer. HEC was successful: about 120 were built. A few of these still survive, and are considered among the oldest electronic computers in the world.

In 1957, Andrew Booth was named the head of the new Department of Numerical Automation at Birkbeck; Kathleen Booth continued to teach programming; it was renamed the Department of Computer Science in 1963. Kathleen Booth, the school said in its 1958 Annual Report, was “developing a program to simulate a neural network to investigate ways in which animals recognise patterns.” The next year’s report noted the development of another neural network, this time for character recognition. Kathleen was way ahead of her time. The Booths left London in 1962 for Canada to teach at the University of Saskatchewan, and later at Lakehead University in Ontario. They also built a copy of their final computer design — which was the first computer ever built in Canada. Dr. Andrew Booth died in 2009 at 91. Dr. Kathleen Hylda Valerie Britten Booth died September 29. She was 100.