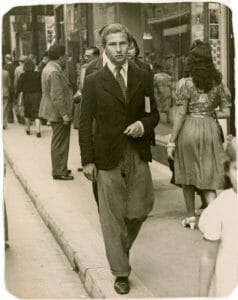

Born in Danzig (now Gdańsk, Poland), Rosenberg was expelled from high school in 1940 because he was a Jew. He had already lost contact with his family, so he decided to flee alone to France — by bicycle and foot to Paris. But that city fell to Germany, so he went to Toulouse. In a shelter there, he met an American, who suggested he meet her in Marseille. He did. Miriam Davenport knew another American, Varian Fry, who was running the Emergency Rescue Committee, helping prominent intellectuals, artists, and scientists escape the Nazi occupation. Rosenberg wasn’t just young, but looked younger and spoke fluent French. With his blond hair and blue eyes, he was perfect to act as a courier and intelligence agent, gathering information as he roamed the city …delivering counterfeited papers, some of which he helped create. Fry’s group helped around 2,000 men and women escape. Rosenberg himself, however, was not one of them. But he was the youngest member, and the last of the group alive.

Justus (pronounced “YOO-stiss”), who Davenport dubbed “Gussie”, wasn’t even paid. But he helped rescue philosopher Hannah Arendt, writer André Breton, musician Pablo Casals, artists Marc Chagall and Max Ernst, author and journalist Arthur Koestler, anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, sculptor Jacques Lipchitz, and author Franz Werfel. Was he intimidated by such intellectual prowess? No: “They were afraid,” he said. “I realized they were like all other human beings.” He got to know many of his charges well: he would sometimes accompany them to the French Pyrenees mountains to escape to Spain on foot. While Rosenberg was often detained, he was never arrested until swept up in a mass arrest. By then, Fry had to leave France, and couldn’t help him. Rosenberg escaped, and later ran into U.S. troops, joined the U.S. Army as a reconnaissance scout, and translator. He earned a Bronze Star — and a Purple Heart.

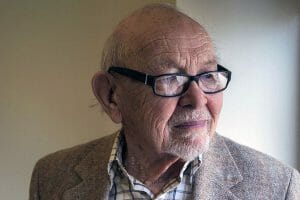

Rosenberg made it to the U.S. in 1946. He found his parents and sister had survived, and was able to see them in 1952. The same year he found and contacted Miriam Davenport, who “simply shrieked with joy” to learn he had survived. How did he do it? “I was very lovable in those days,” he laughed. In 2017 the French ambassador to the United States personally made Rosenberg a Commandeur in the Légion d’Honneur, among France’s highest decorations, for his resistance work during World War II. He shrugged off suggestions he was a hero: “There were so many people who did much more and were much more heroic.” Rosenberg taught at Swarthmore College, The New School, and Bard College, for 70 years — French, German, Polish, and Russian literature. And he wrote a memoir, The Art of Resistance: My Four Years in the French Underground *. Dr. Rosenberg died October 30, at 100.