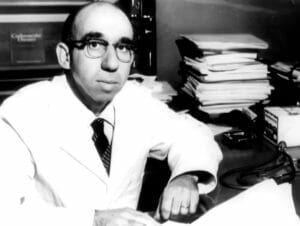

Born in New York City to a dentist and a schoolteacher, Stamler went to school to become a doctor, but he didn’t want to practice, he wanted to do research. His interest: understanding heart problems so they could be prevented. He coined the term “risk factors” to indicate there are many, including, he found, increased salt intake, smoking, lack of exercise, diabetes, high blood pressure, arterial plaque, even hormone levels were factors in heart disease, most of which until that time, doctors hadn’t even considered. Experimental Atherosclerosis, one of Stamler’s first papers, published in 1958, is considered a classic in the field. He also “wrote the first textbook on preventive cardiology,” said Prof. Philip Greenland of Northwestern University’s School of Medicine: Dr. Stamler founded its Department of Preventive Medicine in 1972.

In 1965, Stamler was caught up in an ongoing shame in American history: the House Committee on Un-American Activities summoned him to testify in its investigation of “disloyalty and subversive activities” among citizens. His horrible crime: he believed that Black people had civil rights. After he and a co-worker were subpoenaed by the committee, he and the co-worker sued in federal court, arguing that HUAC was unconstitutional as it exerts a “chilling effect” on the exercise of civil rights. The suit was thrown out by U.S. District Court Judge Julias Hoffman. Dr. Stamler filed an appeal — and, when he went to the hearing, refused to testify pending its resolution and walked out. Stamler was held in Contempt of Congress. The fight continued until 1973, when the government agreed to throw out the charge if Stamler withdrew his lawsuit. “Many people believe the Stamler case and a statistical survey prepared for it by University of Chicago law professor Hans Zeisel was the primary reason HUAC was finally disbanded by Congress” in 1975, said attorney John C. Tucker in his book, Trial and Error.

All along, Dr. Stamler continued his research. The American Heart Association found a lot of merit in his work: it presented him with the Award for Outstanding Efforts in Heart Research in 1964; its Award of Merit in 1967, its Service Award for 1980–81, its Research Achievement Award in 1981, its Distinguished Achievement Award in 1987, and its ultimate, the Gold Heart Award in 1992. In 1990 the AHA also established a new award, which it called the Jeremiah Stamler, MD New Investigator Award. One of his studies involved 300,000 people. “Many, including myself, believe that he is largely responsible for the remarkable decline in coronary heart disease and stroke that occurred in the U.S. over the past few decades,” says Dr. Lawrence Appel of Johns Hopkins University. “Cardiovascular disease remains a major cause of disease and death, but it was far worse.”

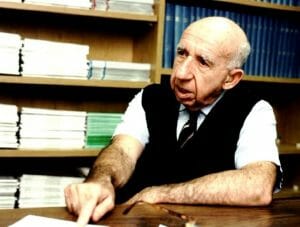

In 2019, the National Institutes of Health gave Dr. Stamler another grant for more research. At the time, he was still teaching and doing research at Northwestern University — and about to turn 100 years old. Why? Because his work “just continued to be interesting.” When would he retire? “I’m only 99 years old,” he said. “I’ve got time.” Dr. “Jerry” He mostly did: Stamler died at his home in Sag Harbor, N.Y., on January 26, at 102. He apparently knew what he was talking about.