Jack’s life was a series of building blocks that make him a star in a specialized field. During World War II, his father was, well, a spy — he intercepted German documents and translated them for American intelligence agencies. He was stationed in Caracas, Venezuela, and that’s where Jack was born. John McAuliffe took his family with him when he was transferred to Honduras, then Colombia, and then finally settled in Fairfax, Va., to work at American University, when Jack was about 8.

As a teen, Jack was so interested in welding that he volunteered as an apprentice with a welder in Virginia, tried college for a year, and then enlisted in the U.S. Navy, where he served on a submarine tender in Dunoon, Scotland, doing maintenance on Polaris submarines. This step set him on a path: he enjoyed Scottish beers, which were much more flavorful than American beers. He bought homebrewing supplies from a Boots pharmacy and, with a copy of Dave Line’s The Big Book of Brewing * (still available today in updated editions), started experimenting with them. He knew he wouldn’t be in Scotland forever, but he wanted good beer wherever he ended up. He shared the brews with his Navy buddies, as well as local friends, who gave him feedback and helped him perfect his recipes. Once back in the U.S., McAuliffe settled in California, finished college in 1971, and got work as an optical engineer.

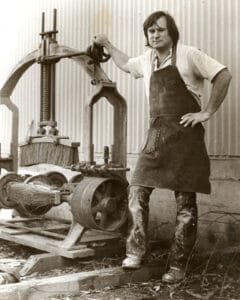

But he still loved beer. He quit his job in 1975, rented property in Sonoma, and used his welding and engineering skills to build brewing equipment. In October 1976, McAuliffe founded the New Albion Brewing Company with Suzy Stern and Jane Zimmerman as business partners, the first microbrewery founded in the United States since the repeal of prohibition. The name honored San Francisco’s Albion Brewing Company, founded in the early 1900s. Jimmy Carter helped spark an interest in better beer by signing a law removing taxes on home-brewed beer in 1978. McAuliffe had gone through historical brewing books at the University of California, Davis, getting recipe ideas. New Albion made its brews in a kettle that produced a barrel and a half — a little over 45 gallons — at a time, in the stainless kettles he had built from cast-offs from dairies and soda manufacturers.

“History is important in the brewing industry,” McAuliffe told an interviewer. “But if you don’t have a history you can just make one up. We made English style ale, porter, and stout. The New Albion Brewing Company, get it? Name, logo and history, bang!” It worked: word spread, and many beer-lovers showed up at his door, willing to work for free to just be there and learn. A strong introvert, McAuliffe had reluctantly let the persistent ones in. One who came knocking was a professor from U.C. Davis who had answered McAuliffe’s questions, Dr. Michael Lewis. When he saw what McAuliffe was doing, he went back and started changing the school’s educational programs: instead of teaching students to work at gigantic beer factories such as Anheuser-Busch, he opened students’ eyes to what could be done on a smaller scale. History was evolving.

There was still a problem: brewpubs were illegal in California, and probably most or even all the other states — a business couldn’t both brew beer and serve it directly to customers. McAuliffe joined forces with Frederick “Fritz” Maytag, who owned Anchor Brewing Co. in San Francisco, founded in 1896 and well known for its “steam” beer. Their mission: to lobby state politicians for a law to allow brewpubs. Without that law, and with his capacity limited to 45-ish gallons at a time, New Albion Brewing continued to struggle — and went out of business in 1982. The law he and Maytag pushed for finally passed and went into effect in 1983, but it was too late: McAuliffe had gone back to work as an engineer.

Still, New Albion sparked a revolution in microbrewing and brewpubs in the United States (see chart below), and McAuliffe is revered as the innovator who provided the spark. Today there are nearly 10,000 breweries in the U.S., most being craft or microbrew, satisfying the thirst of people who wanted something better than the boring watery lagers offered by the brewing giants.

But those inspired by McAuliffe never forgot him. One was Ken Grossman, one of those who came knocking, and then went to Chico to co-found Sierra Nevada Brewing Co., now the third largest craft brewery in the U.S., well known for its Sierra Nevada Pale Ale. In 2010, Grossman invited McAuliffe to visit and do some brewing — and then have lunch at the company’s brewpub. Another admirer was Jim Koch, founder of the Boston Beer Company, best known for its Samuel Adams beer. When the New Albion trademarks came up for renewal, he grabbed them to keep them from going to a big company. He invited McAuliffe for a “brew day” in Boston. McAuliffe directed the recipe, matching the New Albion brew as closely as possible, considering ingredients had changed over the years. They made 6,000 barrels of New Albion, bottled with his old label design, and made it clear it would be the only batch. Once they were gone, Koch handed McAuliffe a check paying him all the profits made: McAuliffe finally got the payoff that he had never received as a pioneer brewer. And Koch gave the trademark ownership back too.

“Jack’s place among United States craft brewers as a change maker and inspiration will be a part of the beer world for generations,” said his daughter, Renee M. DeLuca, toasting him as “the father of the craft beer movement in the United States.” She now owns the New Albion brand, and has partnered with small breweries to bring it back. John Robert “Jack” McAuliffe died at his home in Siloam Springs, Ark., on July 15. He was 80.

You will find more infographics at Statista

You will find more infographics at Statista

Note the starting year of this 2021 chart, when pretty much every U.S. brewery was a large factory. Today, the total is close to 10,000. (Statista)