Miyamura was born in Gallup, N.M., where his parents had settled in 1923. They ran a 24-hour diner a block off Route 66; the family lived in the basement. Miyamura’s teacher couldn’t pronounce his first name (simply: “heh-RO-she”), so he embraced “Hershey” as a nickname. Life was reasonably normal, though his mother died when he was 11, and then there was that World War II thing — and President Roosevelt’s order to relocate those of Japanese ancestry in fear of possible “espionage” or “sabotage” by those Americans. Though the order was not mandatory outside the coastal “military zone,” most areas of the U.S. shipped American citizens off to concentration camps anyway. But not Gallup: residents petitioned the local government to not send their neighbors to the camps. “So we were the only town in New Mexico that the people did not have to go in internment camps,” Miyamura said in a 2014 interview. Town sheriff Dominic “Mickey” Mollica made that official with a public announcement that the Japanese families in Gallup would be treated like his Italian family would be. He was supported by his friend Guido Zecca, the local civil defense leader and commander of the Gallup Veterans of Foreign Wars post. “Hiroshi Miyamura and his hometown had a lot in common,” the Los Angeles Times said in 2017. “They believed in America.” Still, being near the railroad tracks, Miyamura saw train after train pass, full of Japanese-Americans being shipped to camps in Arkansas.

At 16, Miyamura got a job at a service station as a mechanic — and joined his high school’s ROTC program. At 19, with World War II in full swing, he volunteered to join the U.S. Army, asking for assignment to the 442nd Infantry Regiment, comprised almost entirely of second-generation Japanese-Americans (“Nisei”). He trained as a machine-gunner for the Regiment, which would become one of the most-decorated units in U.S. military history. He was quickly discharged — Japan had surrendered — so Miyamura enlisted in the U.S. Army Reserve. Working for the Post Office in Gallup, Miyamura met Terry Tsuchimori, who with her family had been interned in Poston, Ariz., during the war. They married in 1948 and opened a service station, which they ran for 30 years. It was appropriately part of the Humble Oil chain.

In 1950, Miyamura was recalled to active duty for the Korean War, arriving in-country that November. In April 1951, a night attack by Chinese soldiers overwhelmed the Americans, and Miyamura, then a corporal, could see his squad would not be able to hold out much longer. He ordered a retreat, but stayed behind to provide cover; he eventually ran out of ammunition, and disabled his weapon. He ran, but was confronted by a Chinese soldier with a grenade. Severely wounded, Miyamura woke up as a POW, along with his Army buddy Joe Annello — of Italian heritage — and others. It’s estimated in the meantime he had killed more than 50 enemy troops. Annello was wounded and could barely walk, so Miyamura, even though wounded himself, carried him. Chinese troops demanded he leave Annello behind — and both could see that the Chinese were shooting many stragglers. “Put me down, Hersh,” Annello said. “You got to keep going.” Miyamura sadly complied, saying, “I’m sorry, Joe.” The Chinese marched the prisoners 300 miles in five weeks with little food.

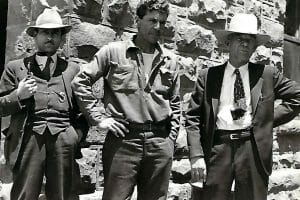

Word of Miyamura’s heroic actions got back to commanders, and he was awarded the highest military decoration, the Medal of Honor. Yet that fact was made Top Secret while Miyamura was still being held — the first time the award was made secret. “If the Reds knew what he had done to a good number of their soldiers just before he was taken prisoner,” Brigadier General Ralph Osborne explained later, “they might have taken revenge on this young man. He might not have come back.” He was held for 28 months, finally released on August 23, 1953. When he arrived back in Gallup 5,000 people were waiting to greet him, led by Mollica, now the mayor, and Zecca, now a state senator. On October 27 Miyamura, who had been promoted to staff sergeant while a POW, was taken to the White House to be awarded the long-delayed Medal of Honor by President Eisenhower. His father lived long enough to see it, and Miyamura said it was his proudest moment to see his father shake Ike’s hand. The city honored him with a statue, and named a high school and interchange on Interstate 40 after him.

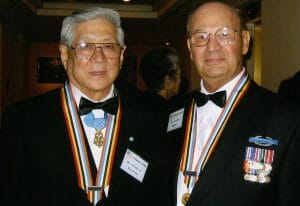

In 1954, Miyamura was working in his service station when a man walked in. “I thought you were dead,” the shaken mechanic said. “I thought you were dead!” said his Army buddy, Annello, who had seen news of Miyamura’s honors. “From the first day we met in that tent,” Annello said later, “we knew we were going to become friends.” And they were, for life, often appearing at events together. In a living history, Miyamura recalled seeing the American flag after he was released as a POW. “I’ve learned what it represents,” he said. “That alone is what makes you feel so humble. So many of these fellas who deserve it never came home to any recognition. There are so many Americans who don’t know what the Medal represents or what any soldier or service woman or man does for this country, and I believe one of these days — I hope one of these days — they will learn of the sacrifices that a lot of the men and women have made for this country.”

With citizens like Miyamura and the many Navajo “Code Talkers” who volunteered to help America and its allies win the war, Gallup calls itself the “Most Patriotic Small Town in America”. After retiring as a mechanic, Miyamura worked with the Wounded Warrior Project and, two weeks before he died, joined the National Board of the State Funeral for War Veterans organization, dedicated to “convince Congress to pass legislation to grant a State Funeral for the last Medal of Honor recipients from the Korean and Vietnam Wars, as a final salute to all the men and women who served.” Terry died in 2014. Hiroshi “Hershey” Miyamura, the second-to-last living Korean War Medal of Honor recipient, died November 29 in Phoenix, Ariz. He was 97, and apparently did not get a state funeral.

—

Author’s Note: One of the volunteer editors was uncomfortable with my use of “concentration camp” in one spot, vs “internment camp.”

I understand the discomfort, but the camps do meet the definition*, and I’ve seen scholars use it in reference to the Japanese. Americans can’t hide their history and expect later generations to learn from it.

* “A camp where persons are confined, usually without hearings and typically under harsh conditions, often as a result of their membership in a group the government has identified as suspect.” (American Heritage)

And in fact President Franklin Roosevelt himself called them concentration camps. In 1946, his Secretary of the Interior, Harold Ickes, similarly told the Washington Evening Star:

As a member of President Roosevelt’s administration, I saw the United States Army give way to mass hysteria over the Japanese…. Crowded into cars like cattle, these hapless people were hurried away to hastily constructed and thoroughly inadequate concentration camps, with soldiers with nervous muskets on guard, in the great American desert. We gave the fancy name of ‘relocation centers’ to these dust bowls, but they were concentration camps nonetheless.

—RC