A Canadian, Kelsey studied pharmacology, and applied for a position at the University of Chicago, which had just started up a pharmacology department. Its director thought “Frances” was a man, and brought Kelsey in. She worked on evaluating new drugs, and earned her Ph.D. In 1960, her husband got a job with the National Institutes of Health, so the couple moved to Washington D.C., where Kelsey went to work for the Food and Drug Administration; her job was to review new drug applications. One of the first applications assigned to her was Kevadon, a sedative. The applicant, the Richardson-Merrell Company, touted the drug’s safety: it had been developed in Germany three years before, and was also effective against morning sickness in pregnant women. The company already had “tons” of Kevadon ready for shipment, and had already distributed 2.5 million sample doses to 1,200 American doctors to try it out.

But Kelsey found some of the details on the application disturbing, and asked for more information. The company supplied it, but complained that Dr. Kelsey was a “fussy, stubborn, unreasonable bureaucrat” who was getting in the way of their marketing timetable. Kelsey researched the drug’s use in Europe, and found a note in the British Medical Journal indicating problems with the drug, and warned Merrell. It dismissed the evidence as “inconclusive.” Kelsey pressed on, demanding that Merrell do more to check the drug’s safety. The back and forth went on for another six months, with Merrell complaining to Kelsey’s bosses, before clear evidence came out of Europe: Kevadon — better known by its generic name, thalidomide — was causing tens of thousands of babies to be born with terrible deformities in Europe, and the term “thalidomide baby” entered the world’s lexicon. Had “tons” of Kevadon been marketed in the United States, it would have had a massive spike in birth defects too. (As it was, before they could be recalled, the samples given to doctors caused deformities in 17 babies in the U.S.) The company was eventually bought out by a larger one to become Merrell-Dow.

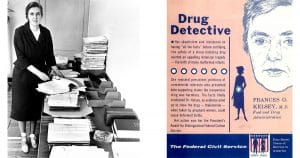

For insisting on safety studies before she would approve thalidomide, Kelsey was hailed as a hero, and the case led to a 1962 law requiring drug companies do more testing to show new drugs are both effective and safe. Dr. Kelsey helped write the testing regulations — and was put in charge of the FDA’s new drug testing and regulation branch. “Her exceptional judgment in evaluating a new drug for safety for human use has prevented a major tragedy of birth deformities in the United States,” said President John F. Kennedy when he signed the new legislation into law; he also presented her with the President’s Award for Distinguished Federal Civilian Service. After a stint as director of the FDA’s Office of Scientific Investigations, she retired in 2005, after 45 years with the agency. In 2010, the FDA presented Kelsey with the first Drug Safety Excellence Award, and named the annual award after her. In 2014, she moved in with her daughter in London, Ont., Canada. She was named to the Order of Canada in June 2015, and Ontario’s Lt. Governor, Elizabeth Dowdeswell, went to her home to present her with the insignia of Member of the Order of Canada on August 7. Less than 24 hours later, on August 8, Dr. Kelsey died. She was 101.