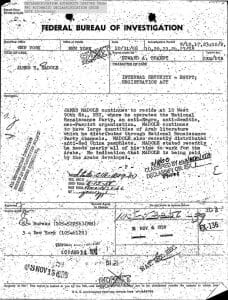

“If there were some prize for ‘Important and Consequential People Who Are Unknown to the General Public’,” said biographer and historian David Garrow, “Ernie would be a top contender.” By day, Lazar first worked in the music industry, from promotions (he received a Gold Record for his work on the 70s disco hit “Born to Be Alive” by Patrick Hernandez) to owning a San Francisco record store. Then he spent “over 22 years for the State of California — at Board of Registered Nursing and at one of our state income tax agencies plus short periods at Dept of Motor Vehicles and the Calif Secretary of State Office.” But in his off hours, Lazar was a prodigious and fastidious researcher, mainly of extremist organizations, providing the results to historians, journalists, authors, and more — for free. Much of his material is available on the Internet Archive, such as his collection of paper FBI files, which he had received by filing Freedom of Information Act requests to the FBI — more than 10,000 of them. The Archive is still working to digitize it all (and taking contributions to help). “Over the past 30 years, literally no one has made greater use of the Freedom of Information Act than Ernie Lazar,” Garrow said.

[Full disclosure: I’ve been donating to the Internet Archive for several years, and a friend of mine was recently brought in as an Archivist there.]

But it wasn’t just 600,000 pages of raw data from the FBI: Lazar would notice correlations and connections to other information he had found, such as published court decisions, and would make notations for the historians who would comb through his files. Lazar may have been driven in part by not knowing who his parents were. He was in his mid 70s before “I learned the identity of my biological mother. Unfortunately, nobody knows the identity of my biological father. So just a mystery to the end.” His single mother gave him to his babysitter’s family, the Lazars, when he was 3.

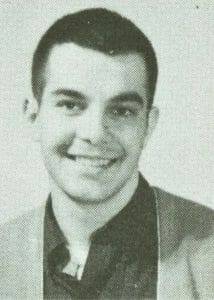

“One of the things I am most proud about is that many dozens of prominent and respected PhD historians, political scientists, sociologists, along with investigative journalists and other researchers have used material from my FBI files collection in their own books, academic journal articles, conference papers, websites, and master’s theses and doctoral dissertations,” he wrote shortly before he died. “And I very much appreciate the kindness and assistance which many of those folks have given me during my 40+ year FOIA research project.” And during that entire time, he worked hard to stay anonymous to avoid confrontations from the groups and individuals he was researching. In all of his files he had no photographs of himself — and never asked the FBI if it had a file on him, especially considering he was likely the agency’s most prodigious file requester. “Later, when the FBI offered requesters the option of receiving FOIA releases as PDF files on CD or DVD instead of just paper docs, I re-submitted hundreds of requests so that I could share them online with everyone on Internet Archive.”

Lazar knew death was coming: he was in hospice care for 2 years with end-stage renal disease. “Although my journey is coming to an end,” he wrote online, “please be sure that you and your friends and family members are encouraged to vote in November. The stakes for our democracy are very high,” he said. “Please continue the fight to make our country live up to its ideals!” Lazar, who never finished college, died at his home in Palm Springs on November 1, at 77.