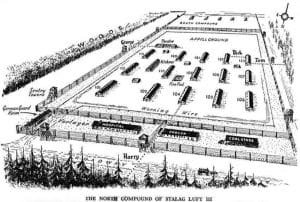

Born in Crediton, Devon, England, in World War II Churchill was the pilot of a Handley Page HP.52 Hampden bomber in the Royal Air Force’s No. 144 Squadron — and, in September 1940, was shot down by fighter planes. He parachuted into the Netherlands, was captured, and sent to Stalag Luft III, a Luftwaffe-run prisoner of war camp established in the German province of Lower Silesia, near the town of Sagan (now Żagań, Poland). The site was selected because its sandy soil made it difficult for POWs to escape by tunneling. A prisoner there, RAF Squadron Leader Roger Joyce Bushell, proposed to take on that challenge; Air Commodore Herbert Martin Massey, the senior British officer imprisoned at the camp, authorized the escape plan. Churchill joined as an eager worker to help dig tunnels. Several were dug, dubbed “Tom”, “Dick”, and “Harry”.

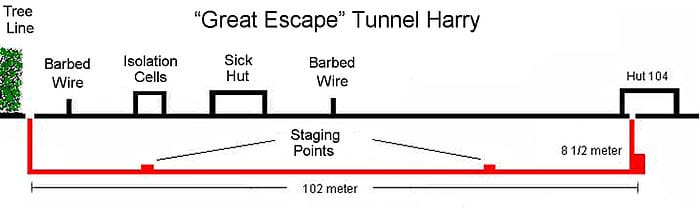

Indeed it was difficult: the prisoners used clever methods to shore up the wet sand. Among other items, they used 4,000 boards from their beds, 90 complete double bunk beds, 635 mattresses, 192 bed covers, 161 pillow cases, 52 twenty-man tables, 10 single tables, 34 chairs, 76 benches, 1,212 bed bolsters, 478 spoons (plus 1,219 knives and 582 forks), 246 water cans, 30 shovels, 300 m (1,000 ft) of electric wire to power 69 lamps, 180 m (600 ft) of rope, 3,424 towels, 1,700 blankets, and more than 1,400 powdered milk cans. After the Germans found one of the tunnels, escape plans were hurried: on March 24, 1944, 76 men got out through tunnel “Harry” — including Churchill, paired with squadron leader and engineer Bob Nelson. Only three of the escapees made it all the way back to England; the other 73 were captured, including Churchill and Nelson, found two days later in a hay loft. A furious Adolph Hitler ordered that all of the escapees be shot — along with the camp Commandant, the architect who designed the camp, the camp’s security officer, and all the guards on duty at the time. Hitler was warned that killing the prisoners would be a war crime, and he relented a little: he ordered SS head Heinrich Himmler to shoot “more than half” of the prisoners, and 50 of them were shot by the Gestapo after interrogation. That included the lead planner, Bushell, but not Churchill and Nelson, because of their names: German commanders were worried Dick might be related to Britain’s Prime Minister Winston Churchill (which he refused to confirm or deny), and Bob might be a descendant of Vice Admiral Horatio Nelson. They, and the 21 other survivors, were returned to camp.

If the story sounds familiar, it’s because another prisoner, Paul Brickhill, who had been a journalist before the war, was outraged over the war crime and pledged to document it. His resulting book was somewhat fictionalized: The Great Escape, which was made into a successful Hollywood movie by the same name in 1963. Was it a mistake, considering the deaths? Dick Churchill didn’t think so. “It was a worthwhile venture,” he said. “You could become a dope, and sit out war. Or you try to do something that’s likely to get you out and give you a chance of getting home — after all, three did get home. If nothing else, you are doing something towards the target of getting out and getting back to what you were doing before, whether it’s flying fighters or dropping bombs.” Plus, working 30 feet underground in the effort “gives you a purpose.” After the war, Richard “Dick” Churchill went back to his home town in Crediton, and eventually was the last of the participants of the real “Great Escape” alive. He died in Crediton on February 13, about six weeks shy of the 75th anniversary of the escape. He was 99.