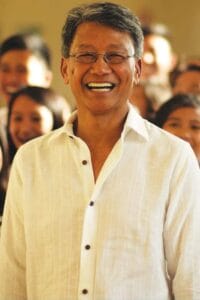

His story is almost a storybook rags to riches saga. Born to a rice farmer, as a child Banatao walked barefoot to school on a dirt road in Iguig in the Cagayan Valley of the Philippines. He learned math by manipulating bamboo sticks. His father may have been poor — their home didn’t even have electricity — but he could see his son had something special about him. Normally in the valley, children would leave school after the sixth grade to work in the fields, but Banatao’s father told him to stay in school. After high school, Banatao was accepted into the Mapúa Institute of Technology in Manila — and graduated cum laude with a bachelor’s degree in Electrical Engineering.

That brought Banatao several job offers; once he saw the salary offered, he turned down a job at Meralco — the Manila Electric Company — to instead sign on as a trainee pilot for Philippine Airlines. There he caught the attention of one of that company’s suppliers: he was poached by Boeing to work as a design engineer for their new airplane under development — the 747. That got him to the U.S., where in 1972 he earned a Master of Science degree in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at Stanford University. He also joined the Homebrew Computer Club, where he met Steve Wozniak. He was in the right place, at the right time, with the right education, and placed the right bet: all-in on the personal computing industry.

He worked with National Semiconductor, the chip company Intersil, and Commodore International. He designed a 16-bit microprocessor-based calculator in a way that no one had done it before: it was all in a single chip, which was a huge innovation because it dramatically reduced manufacturing costs, product size, and power usage, while simultaneously increasing product reliability. He went on to develop the first 10-Mbit Ethernet chip, the first system logic chipset for the IBM PC/XT and PC/AT computers, and the local bus concept, which let high-speed components like graphics and networking pass to the CPU at full speed, instead of being bottlenecked by the shared pathways of previous system architectures. In all, about 30 percent of the core subsystems inside every PC was initially designed by Banatao — particularly the parts that make them faster and cheaper.

In 1984, Banatao joined with a partner to make motherboards for PC manufacturers, then started another company based on the next thing he developed: a 5-chip set that was fully compatible with the IBM PC/AT. That was Chips and Technologies, which was such a hit he booked $12 million in orders …in the first four months of operations in 1985, which is the equivalent to about $36 million today. As graphics was overtaking character-based displays in 1989, he started S3 Graphics based on the next thing he designed: one of the first GUI accelerator chips for PCs. By 1996 S3 was beating out its biggest competitor, Cirrus Logic. Banatao started cashing in: he sold C&T to Intel for ~$430 million, which he used to start his own venture capital company, Tallwood. He sold S3 for another $300 million, and one of his first investments through Tallwood brought in more than $1 billion.

And all that doesn’t even include his involvement in commercializing the military’s Global Positioning System once it was declassified. In the early 1980s while working at National Semiconductor, Banatao led the team that designed the first single-chip, CMOS-based GPS receiver, dramatically reduced size, power consumption, and cost of GPS devices, which made for a huge market all by itself. His work enabled GPS to move into commercial aviation, automotive navigation, surveying and mapping, and then to handheld and consumer devices. The resulting explosion of navigation devices, smartphones, logistics tracking, and location-based services depends on this transition from large, heavy, military-specific devices to efficient ICs — GPS on a chip. In short, Banatao repeatedly showed up at the same inflection point: taking a powerful but expensive technology and making it cheap enough to change the world in profound ways.

Banatao didn’t hoard his money, he put it to work to “pay it forward.” He co-founded the Philippine Development Foundation to fund STEM education for students from low-income backgrounds; provide mentorship and networks, not just scholarships; and to create a pipeline from Philippine universities to global tech ecosystems. PhilDev programs pair students with industry mentors, internships, and real-world exposure — the sort of advantages Banatao himself lacked early on. Banatao was notably low-profile about his giving. He avoided splashy naming opportunities and instead focused on endowing engineering and science programs, supporting entrepreneurship education in the Philippines, funding long-term capacity, not short-term relief. His point was to keep the focus on outcomes rather than on himself, which is why you likely never even heard of him.

But if you did, it was because he wanted to model that he was an immigrant to the U.S. who gave back. A technologist himself, not merely an investor. And someone who came from poverty, yet navigated elite technical spaces. For others from humble backgrounds, that mattered more than monetary rewards: he proved that the “rags to riches” story is still possible. He didn’t merely escape poverty: he engineered paths for those who came up behind him. In 1993, Banatao received the highly respected Ellis Island Medal of Honor, which is awarded to U.S. citizens who contribute significantly to an ethnic group or country. Diosdado “Dado” Banatao died December 25 at Stanford Medical Center from an unspecified neurological disorder. He was 79.