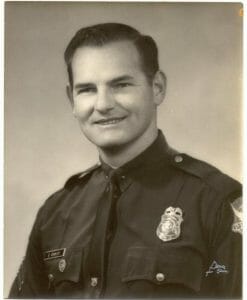

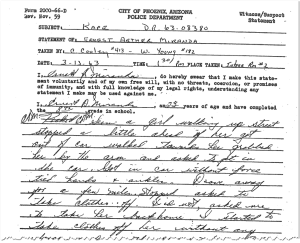

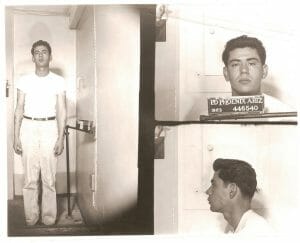

A police officer in Phoenix, Ariz., since 1958, Cooley was promoted to Detective in 1962. In 1963, he and his partner, Wilfred Young, were investigating a kidnap-rape, and asked Ernesto Miranda to come to the station for questioning. Miranda and his car matched the victim’s description, but “Seeing a car driving in a neighborhood doesn’t give you probable cause” for arrest, Cooley said later, so Miranda was not arrested or handcuffed. He was put in a lineup with three other men and presented to the victim; she picked out Miranda as her attacker, and Miranda verbally confessed. He then put his confession in writing, affirming “this statement has been made voluntarily and of my own free will, with no threats, coercion or promises of immunity and with full knowledge of my legal rights, understanding any statement I make can and will be used against me.” But he had given his oral confession before that information was presented to him. He was arrested and charged.

At trial, Alvin Moore, his court-appointed attorney, objected to the confession, noting the part about “voluntarily” and “full knowledge of my legal rights” was printed on the form, not written by Miranda, and that he had not been told that he had a right to remain silent and have an attorney represent him. The objection was overruled by Judge Yale McFate, and Miranda was convicted and sentenced to 20-30 years in prison. He had previous convictions for burglary and attempted rape.

Moore appealed Miranda’s conviction. Cooley swore he did not force Miranda’s confession, and was indignant to suggestions that he had done so. The Arizona Supreme Court upheld the conviction. In June 1965, Miranda appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. The Supreme Court accepted the appeal, combining it with three other similar cases. In a narrow 5-4 decision, Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote the opinion overturning Miranda’s conviction, writing:

The person in custody must, prior to interrogation, be clearly informed that he has the right to remain silent, and that anything he says will be used against him in court; he must be clearly informed that he has the right to consult with a lawyer and to have the lawyer with him during interrogation, and that, if he is indigent, a lawyer will be appointed to represent him.

Miranda was not released, he was re-tried without the confession as evidence. He was again convicted, and again sentenced to 20-30 years in prison. After the Supreme Court decision, police officers actually read a suspect their rights, as heard during pretty much every police procedural show ever since: “You have the right to remain silent. If you give up the right to remain silent, anything you say can and will be used against you in a court of law. You have the right to an attorney and to have an attorney present during questioning. If you cannot afford an attorney, one will be provided to you at no cost. During any questioning, you may decide at any time to exercise these rights, not answer any questions or make any statements. Do you understand these rights as I have read them to you?” It’s read so that it can’t be argued the officer forgot part of the warning, and so they won’t be required to recite the warning from memory in court when asked; they can read it there, too.

Despite that the U.S. Supreme Court decision applied to three other men in addition to Miranda, the warning quickly became known as the Miranda Warning, and was printed on cards for cops to read. Once released from prison on parole in 1972, Miranda would sell autographed copies of the card for a dollar or two. He was stabbed to death while gambling in 1976. Detective Cooley was not tainted by the conviction reversal: he was promoted to Captain, and retired from the department in 1978. He went on to teach police officers at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, and was a Commander of the Arizona Highway Patrol. He also volunteered at the Phoenix Police Museum, which has a permanent display about the department’s connection to the Miranda Warning. Carroll Franklin Cooley died on May 29 at his Phoenix home from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. He was 87.