After starting as a reporter in his teens, Redmont earned his bachelor’s degree at the City College of New York, then his Master’s from the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism in 1939 — and was awarded the school’s highest honor, the Pulitzer Traveling Fellowship. But World War II broke out, so Redmont enlisted in the Marines and served as a Combat Correspondent, and was awarded a Purple Heart for combat wounds. After the war, he was hired by a new news magazine: what would become U.S. News & World Report, where he was an award-winning foreign correspondent.

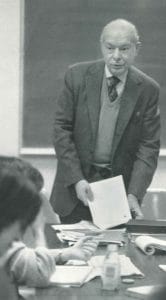

In 1950, Redmont was called before the House Un-American Activities Committee, which was investigating the supposed infiltration of “communists” into American society. He was asked to testify about William Remington, a former Commerce Department official, but Redmont had no knowledge about any transgressions by Remington, so the tables were turned on him. Why did he change his name, for instance? He was born a Rothenberg. Redmont changed his name so anti-Semitism wouldn’t harm his career, he said. Based on that, Redmont was fired by U.S. News & World Report, and despite being an American citizen who was born in New York, the U.S. State Department canceled his passport — while he was overseas. It took years of fighting to get it back so he could come home. Meanwhile, living in Paris, Redmont had a hard time getting work. “At one point,” he said later, “I set a record in amassing the largest number of jobs in Paris, with the lowest aggregate income.” He eventually found work again as a reporter, and won the 1968 Overseas Press Club award for his reporting on the peace talks to end the Vietnam War. He also was head of the English desk of the Agence France-Presse for years, and later served as dean of Boston University’s college of communication. He retired in 1986, and died January 23, from congestive heart failure. He was 98.