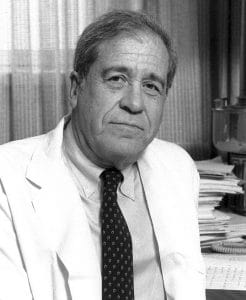

Born and raised in Pittsburgh, Pa., Fisher graduated from medical school at the University of Pittsburgh in 1943, and became a surgeon. Pitt Med School needed teachers, so Dr. Fisher signed on as the school’s first full-time member of the Department of Surgery. In 1953, he established the university’s first Laboratory of Surgical Research, the school says, “based on his firm belief that evidence gathered through scientific inquiry should serve as the basis for advancing patient care.” As he studied more, he became interested in cancer research, especially breast cancer, because of the treatment dogma that had driven treatment of that disease since ancient Greece: the mastectomy, or surgical removal of the breast. That was “refined” later to the radical mastectomy, removing not just the breast, but the lymph nodes and chest muscles, under the theory that cancer may have spread to those areas. That surgery was relatively unchanged since Dr. William Halsted developed it in …1894.

The data-driven Fisher questioned the conventional wisdom, not believing that cancer had an orderly spread from a single point outward. He thought it was more likely that cancers spread by sending out cells, which could then grow in various other parts of the body. If that was the case, then a radical mastectomy wouldn’t help if the cancer had already escaped the breast, and was way too invasive of a procedure if it had not. A “lumpectomy” would be better in that case: a simple removal of the cancerous tissue itself, followed by radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and/or hormonal therapy to kill the cancer cells that spread through the body in the bloodstream. Fisher was widely derided and attacked for the very idea. “He was thought to be a traitor,” said Dr. Siddhartha Mukherjee. “He was thought to be hacking away at the very foundations of this discipline. He was denied grant funding, he couldn’t recruit surgeons for the trial.”

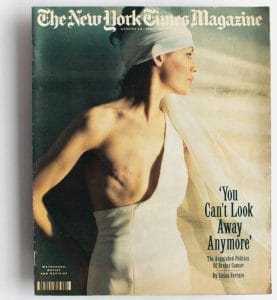

Who was behind him, then? The women who were at the other end of the knife. Mastectomies were hardly discussed in “polite company.” They forced the discussion: the mystery — and often shame — associated with them was a point of contention in the women’s movement. The groundswell forced a new look at the “standard” treatment. It wasn’t even until 1993 that a photo was published to the public showing the sobering results of the operation — on the cover of the New York Times Magazine with the caption, “You Can’t Look Away Anymore”. “No one had seen this scar before, unless you had it, or a close family member had it,” said NYTM art director Janet Froelich, who chose the photo for the cover. “Nothing had caused quite as much of a stir. It was one of the all-time most controversial, and a gatherer of a lot of letter writing.” Yet most of those letters were positive; in 2003 and again in 2011, Life magazine named the portrait, “Beauty Out of Damage”, one of the “100 Photographs that Changed the World”.

“Breast cancer is a scientific problem,” Dr. Fisher said. “It is not an intellectual exercise or an emotional problem. And therefore the data which determines what or what not should be done must be obtained, and analyzed in a scientific way.” Fisher proved to be right: with his data-driven treatment protocols, the 10-year survival rate for breast cancer tripled, from 25 percent in the mid-1940s to 50s, to 76.5 percent at the turn of the century. “Bernard Fisher was a titan,” says Arthur Levine, Dean of the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. “His research improved and extended the lives of untold numbers of women who suffered the scourge of breast cancer. His work overturned the dominant paradigm of cancer progression and, to the benefit of all, demonstrated the systemic nature of metastasis. This work offered us great insight into the biology of all cancer.” In 1985, Fisher was given the Lasker Award for medical research “for his pioneering studies that have led to a dramatic improvement in survival and in the quality of life for women with breast cancer.” By then radical mastectomies for breast cancer had declined by 90 percent. Dr. Fisher died on October 16. He was 101.