After growing up in Montana, McDonald graduated from Montana State University with a degree in chemical engineering in 1959. He quickly got a job with Thiokol to work on designing rockets for the Minuteman missile. In 1974, Thiokol won a contract to build the solid rocket boosters for NASA’s Space Shuttle program, and Thiokol put McDonald in charge of the project. In 1982, the company merged with Morton Salt maker Morton-Norwich, and renamed Morton Thiokol.

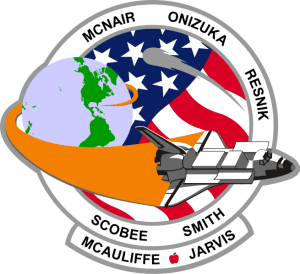

In January 1986, McDonald was at Cape Canaveral for the launch of Shuttle mission STS-51-L. His job: sign the form certifying that the SRBs, one strapped onto each side of the main fuel tank, were ready to fly. “And I made the smartest decision I ever made in my lifetime,” he said later. “I refused to sign it. I just thought we were taking risks we shouldn’t be taking.” The risk: it was very cold at the launch pad, and ice was hanging from various areas of the shuttle Challenger and its launch system. The O-rings sealing the booster joints, McDonald knew, stiffened when they got below 53 degrees (11.6 C), reducing their effectiveness. Well before then, “we recommended not launching below 53 degrees Fahrenheit. And we put that in writing and sent that to NASA.” But NASA pressed for Challenger’s launch despite a predicted ambient temperature at launch time of 27 degrees (–3 C). “If anything happens to this launch,” McDonald told his NASA counterparts, “I wouldn’t want to be the person that has to stand in front of a board of inquiry to explain why we launched.” Under NASA pressure, Thiokol officials overrode McDonald and approved the launch anyway; the flight lasted just 73 seconds before Challenger exploded in a fireball. The seven astronauts aboard the spacecraft survived the explosion: at least three of them activated emergency oxygen supplies. But they did not survive the impact when their capsule hit the Atlantic ocean’s surface.

Still, McDonald thought the explosion was caused by an engine failure until he saw launch footage showing flame shooting out of the SRB joint — right at the giant fuel tank (see photo in archive). NASA covered up the reasons for the disaster, and President Ronald Reagan empaneled the Rogers Commission to look into the causes. McDonald sat in back at an early meeting and heard a NASA executive lie about what happened. He spoke up to contradict the assertion, and commission chair William Rogers, a former U.S. Attorney General, said, “Would you please come down here on the floor and repeat what I think I heard?” He did, helping the investigators narrow their focus*.

Morton Thiokol immediately demoted McDonald, but when a congressman introduced a resolution stripping the company of future NASA contracts unless they let their engineers speak frankly to the commission, the company promoted McDonald to lead the re-engineering of the SRBs. Shuttle missions resumed with his new design after a 32-month hiatus — and Thiokol quietly pushed McDonald out of high-level tasks. He retired from the company in 2001 after a 42-year career — and then wrote (with space historian James Hansen) the definitive book on the causes of the disaster: Truth, Lies, and O-Rings: Inside the Space Shuttle Challenger Disaster (Amazon affiliate link), which was based on 1,400 pages of handwritten notes he decided to make at the time. He also went on the lecture circuit to speak about ethics and decision-making. McDonald lived by the motto of “The Seven R’s”: “Always do the Right thing for the Right Reason at the Right time with the Right people, and you will have no Regrets for the Rest of your life.” Of his decision to blow the whistle on NASA and his bosses, McDonald said, “Regret for things we did is tempered by time. But regret for things we did not do is inconsolable.” Even NASA (eventually) revered him, bringing him to speak in 2012. “I made the smartest decision I made in my lifetime,” he repeated. “I’d say second smartest if my wife was here.” Allan James McDonald died on March 6 after a fall caused a head injury. He was 83.

—

*Author’s Note: Meanwhile, another Thiokol engineer, Roger Boisjoly, was leaking inside information about the O-rings to commission members and the media. “I fought like Hell to stop that launch,” Boisjoly told NPR three weeks after the explosion, under condition of anonymity. “I’m so torn up inside I can hardly talk about it, even now.” His family released NPR from their pledge to keep their source confidential after he died in 2012.

Examples of NASA’s pressure: when Thiokol recommended delaying launch, NASA’s George Hardy responded, “I am appalled. I am appalled by your recommendation.” Shuttle program manager Lawrence Mulloy was even stronger: “My God, Thiokol,” he said. “When do you want me to launch? Next April?” Still, the Thiokol engineering team — McDonald, Bob Ebeling, Arnold Thompson, and Boisjoly — stood firm against upper management’s kowtowing to NASA pressure, and a senior Thiokol official approved the launch over their objections.

Boisjoly refused to go back to work for Morton Thiokol. He founded a forensic engineering firm and was frequently invited to speak on leadership ethics. Ebling died in March 2016. I could not find any current status for Thompson.

Mulloy was “reassigned” by NASA, but refused the offer to move to NASA’s Washington headquarters (from Marshall Space Flight Center) and retired in July 1986 — at age 52. He denied any wrongdoing in the disaster.

Hardy, who also worked at Marshall, also took early retirement.