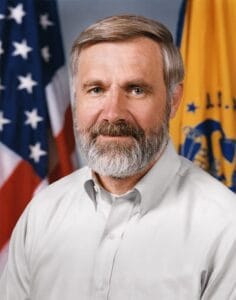

Born and raised in Iowa, Foege’s family moved to Washington when he was 9, and by 13, working in a pharmacy, he became interested in science. After spending 3 months in a body cast at 15 to solve a hip problem “in the days before television,” Foege (pronounced “fay-ghee”) read a lot — “about Albert Schweitzer, and medicine, and Africa, and all of this became very interesting to me.” He decided he’d like to become a doctor and heal people in Africa. It was a “time of reflection and reading that I might not have had without that physical problem.” He went to Pacific Lutheran College (now University), and was particularly taken by his Biology teacher, William Strunk, “who was a man I’ve never seen the likes of.” As Strunk walked into class, he would already be lecturing. “He would go to the board and actually write with both hands simultaneously, putting up phyla and families and classes and genera. He would still be talking as he left the room.” Foege worked as Strunk’s lab assistant, and even did yard work at his house, to absorb as much as he could.

Foege went to medical school, deciding to specialize in internal medicine. During residency, he got a call from the Centers for Disease Control: would he be interested in working there? “I abandoned my idea of going into internal medicine, and went to CDC in the [Epidemic Intelligence Service] class of 1962.” He was sent to India on a temporary duty assignment, and learned that the Peace Corps doctor assigned there was ill, so Foege volunteered to replace him. That job “turned out to be important in so many ways. I saw global health close up.” And, he added, “I saw my first cases of smallpox,” a horrible and highly contagious disease that has existed in humans since at least 1500 BCE — it was found in Egyptian mummies. Even in the 20th century, around 30 percent of sufferers would die: smallpox is estimated to have killed up to 300 million people in the 20th century alone. Those who do live carry the scars of the blisters for life; many are blinded. Dr. Foege was deeply affected by seeing the disease close up.

Smallpox is actually the first disease to have a vaccine. British physician Edward Jenner demonstrated that an infection with the relatively mild cowpox virus conferred immunity against the deadly smallpox virus — in 1796. The very word “vaccine” comes from “vaca,” Latin for cow, a nod to the animal being the source of the protection. The smallpox vaccine of course was highly developed and effective by the 20th century.

Foege’s next temporary duty assignment was to go to the Kingdom of Tonga, the only island nation in the South Pacific to not have been colonized by European powers, where the King was amenable to participate in a vaccine study against smallpox. “Tonga had not done routine vaccinations since 1905, so it provided a virgin population in which you could measure antibodies and so forth,” Foege said. “We wanted to evaluate the effectiveness of different dilutions of smallpox vaccine…. It turned out to be a very good study that demonstrated you could dilute the vaccine one to fifty, and that you would still get uniform take rates. We also demonstrated that the vaccinations could be given with the jet injector, which didn’t require special training in technique to have the vaccinations come out the same with every person. It was easy to train a person to use a jet injector. This turned out to be a very important study.” He himself later used the injector to administer more than 11,000 smallpox immunizations in a single day.

During this time, Foege read an article by virologist Dr. Thomas Weller of the Harvard School of Public Health. “I had no idea at the time that Tom Weller was a Nobel laureate [in Physiology or Medicine in 1954, for his work on the polio virus], but when I read the article, I knew I wanted to know him, because he was saying in the article things that I believed.” He left the CDC and enrolled at Harvard to earn his Masters of Public Health, studying under Weller. One of the studies he wrote and presented was to discuss the feasibility of actually completely eradicating smallpox in the world, but he didn’t think at the time it was possible to vaccinate everyone to accomplish the idea. He graduated in 1965, and went to work in Nigeria. His team had a very small amount of smallpox vaccine, and a lot of people to give it to. How would they decide who? The team sent runners to villages to find out if there were any outbreaks, and found where the cases were. There was not enough vaccine to immunize everyone even in those villages.

Foege had to think. “We literally asked ourselves, ‘If we were a smallpox virus bent on immortality, what would we do?’ The answer was to find susceptible hosts in order to continue growing,” he said. “So we figured out where people were likely to go because of market patterns and family patterns. We chose three areas that we thought were susceptible, and we used the rest of our vaccine to vaccinate those three areas. That used up all of our vaccine. We didn’t know it, but in two of the areas, smallpox was already incubating, but by the time the first clinical cases appeared, those areas had been vaccinated. And so smallpox went no place. By three or four weeks later, the outbreak had stopped. And we had vaccinated such a small proportion of the population!” It was a revelation, which led to being more strategic with “surveillance/containment,” which later became known as “ring vaccination” — strategic use of vaccine rather than trying to vaccinate everyone. It was a major breakthrough, but it still needed to be tested for a larger area.

“We talked to the Ministry of Health. It was a very crucial time, because war was being talked about every day. The Ministry of Health said that in the eastern region, they were willing to change the whole strategy against smallpox. We could put all of our attention on finding smallpox and containing each outbreak. Five months later, when war fever was at a peak, we were working on the last known outbreak in that entire region of 12 million people. In five months, we’d cleared out every outbreak. We were working on the last outbreak when war broke out.” It was July 1967 and, Foege found out months later, “There was never any smallpox in the area of fighting during the Nigerian-Biafran civil war.” His strategy worked. He tried to keep working in the country, but was forced out, first being arrested by Biafra, and then by Nigeria. He returned to the CDC, where he began to work on “selling” his new eradication idea to the top brass there.

“Some people were sold immediately,” he said, such as Donald R. Hopkins, who was going to Sierra Leone, “which had the highest rates of smallpox in the world. Sierra Leone at that time had poor communications and transportation. [Hopkins] started out from the beginning doing surveillance/containment. He never bothered with mass vaccination.” That proved Foege’s idea on an even larger scale. “Other people were more reluctant, and I can understand that: [CDC] had sold most of the governments on universal vaccination.” Much to his surprise, the hardest country to clear was India: he went there himself. “In Bihar, India, in one week, we had over 11,000 new cases of smallpox. I mean, it was just overwhelming. But we went from that high in May of 1974, to zero for the entire country of India in 12 months.” And “gradually, place after place did do this, and the bottom line was, we were able to eradicate smallpox in five years. In country after country, smallpox disappeared. I’m quite sure that in any geographic area where they converted to surveillance/containment, 12 months later, it was smallpox-free. Nigeria had its last cases in May of 1970, and the whole 20-country West African area had smallpox disappear in three years and five months, a year and seven months before the target, and under budget.”

Dr. Foege was made director of the Centers for Disease Control in 1977 — the same year that the last naturally occurring case of smallpox occurred, in Somalia. It was the first infectious human disease to be completely eradicated, ever. The last person to die from it, on September 11, 1978, was Janet Parker, a medical photographer at the University of Birmingham Medical School in the U.K., who was infected by a leak in a lab, which made it clear that it was very dangerous to keep samples in labs. The U.S. and Russia still maintain such samples. The World Health Organization declared smallpox eradicated on October 26, 1979.

But there was one thing that bothered Foege: they were not just trying to eradicate smallpox. “We must remember that this was always a smallpox and measles program,” he said in 2006. Once smallpox was eradicated, “we assumed that USAID would see the benefit of continuing the measles part of this, because measles deaths had been greatly reduced.” Yet, USAID, which was funding the effort, refused. “It was a decision, as far as I can tell, of one person at USAID, who was new, who didn’t have an emotional commitment to the measles vaccine program and who wanted to do his own things.” The world came so close, but …politics. And now it’s ramping up again.

In 2006, the University of Washington, where Foege received his medical degree, dedicated the William H. Foege Building, which houses the university’s School of Medicine’s Departments of Bioengineering and Genome Sciences. It was largely financed by a $70 million grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. “We turned to Bill Foege early in the history of our foundation,” Bill Gates said at the time. Foege played a leading role in helping the foundation craft its strategy to improve worldwide public health. He left the CDC in 1983, and later joined Emory University in Atlanta’s Rollins School of Public Health as Professor of International Health. He spent 10 years as a Senior Fellow at the Gates Foundation, influencing its decision to spend $750 million to start the Gavi Vaccine Alliance, which provides childhood vaccination to the half of the world’s children who would otherwise not be vaccinated. And in 2012, President Barack Obama awarded Foege the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, but what are such honors compared to the knowledge that his ideas led to the eradication of a terrible disease, saving millions?

The successful eradication of smallpox, Dr. Foege said, “shows the value of having young people involved in the project. Julie [Julius] Richmond, the former Surgeon General, once said that the reason smallpox eradication worked is that the people involved were so young they didn’t know it couldn’t work. And you know, that’s probably true.” Also, he once said, “There is something better than science. That is science with a moral compass, science that contributes to social equity, science in the service of humanity.” Dr. William Herbert Foege died on January 24 from congestive heart failure at his home in Atlanta, Georgia. He was 89.

Author’s Note: Most of Dr. Foege’s quotes are from a 2006 oral history recorded by Emory University, which helped me to tell much of his story in his words.