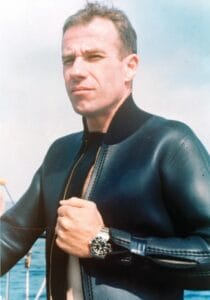

After growing up in Pennsylvania, where he loved to swim, Croft joined the U.S. Navy at 17 as a diver, which had a huge impact on his life. After deployment on multiple submarines, he served at the Groton Submarine Escape Training Tank in Connecticut. He was an instructor, teaching prospective submariners how to escape from a disabled submarine, which could be resting on the sea bottom. As part of that work, Croft spent five hours per day, five days a week working at the 118-feet deep 250,000-gallon submarine escape training tank, which provided him a special opportunity to engage his curiosity about something he had been doing since well before his Navy days: holding his breath underwater.

While living in Narraganset Bay, R.I., as a child, Croft developed a technique to stay underwater for much longer than his peers: “air packing.” Also known as lung packing or glossopharyngeal inhalation, it’s a way to push more air into the lungs than normal for a “full” breath — by 10–30 percent for seasoned practitioners. Doing it routinely also helps expand the rib cage over time to enable deeper breaths. Obviously, this could aid survival for someone who had to escape disabled submarines, but it’s also effective for breath-holding competitions, such as freediving. (It can also be dangerous, as it can lead to syncope (fainting) due to reduced venous return, and also pneumothorax — air escaping into the pleural space between the lung and the chest wall, which can result in a collapsed lung.)

Croft, being in excellent health, used lung packing to his advantage. As a teen, he could hold his breath while underwater for 1-1/2 to 2 minutes. After a year working in the tank, he was able to hold his breath for over 6 minutes, dropping to the bottom and sitting there for over three minutes, and then returning to the surface at a relaxed pace. With his increasing level of comfort in holding his breath, Croft wanted to see how far he could go beyond the tank’s 118-ft depth. In 1967, with the encouragement of his fellow instructors, Croft set out to discover how deep he could dive while holding his breath. Over an 18-month period, in competition with French diver Jacques Mayol and his friend, Italian diver Enzo Majorca, Croft established three freediving depth records:

- Feb. 8, 1967: 212 feet (64 m) off the coast of Florida, making Croft the first person to ever dive below 200 feet while breath-holding, which at the time scientists believed was the physiological depth limit for breath-hold diving.

Shortly afterward, Mayol broke that record. In 1968 Croft set new records, again off the coast of Florida, and supervised by Navy divers:

- 217 feet (66 m)

- 240 feet (73 m) on August 17, after which he retired from competition.

These were not mere stunts: Navy research scientists used him and his abilities as a test subject, leading to a research paper published in the journal Science: “Pulmonary and circulatory adjustments determining the limits of depths in breathhold diving.” (1968)

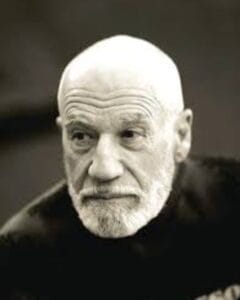

After retiring from the Navy, Croft worked for Tarrytown Labs, which manufactured recompression chambers for oil rig divers in the Gulf of Mexico, and then worked in various management positions, including for Ingersoll Rand, and finished his working life as a videographer creating training videos for Dresser-Rand, and traveled the U.S. full time in an RV with his wife. They settled back in Pennsylvania, and Croft wrote his autobiography, Navy Diver, Submariner and Father of American Freediving *. In 2016, he received a NOGI Award (“the Oscar of the ocean world”) in the Sports & Education category from the Academy of Underwater Arts and Sciences for his work as a test subject to understand how the human body reacts in such dives. Robert A. “Bob” Croft died in Lebanon, Pa., on January 9. He was 91.