Born in Cleveland, Ohio, Stofan went to the same college his parents had graduated from in 1928: Hiram College. He met his own wife there; he and Barbara married in 1955. In 1958, he earned both a B.A. in mathematics from Hiram and a B.S. in mechanical engineering at Carnegie Mellon University, and then did graduate work in both math and engineering at Case Western Reserve University before leaving to accept a new opportunity. He was hired at the Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory just before it was renamed to the Lewis Research Center when it was absorbed by the newly formed National Aeronautics and Space Administration: NASA. To explain his importance, I have to teach you a little rocket science.

The early days of rocketry were dangerous ones. At NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in the late 1940s and early ’50s, engineers developing the Corporal and Sergeant missiles were learning by trial and error — and much of that “error” ended in massive fireballs. The Corporal, America’s first operational guided ballistic missile, used a liquid propellant combination of red fuming nitric acid and aniline (later furfuryl alcohol). Those chemicals were hypergolic — they ignited the instant they touched — but they were also highly toxic, corrosive, and unstable. The plumbing and seals of the era couldn’t reliably contain them, and the slightest leak or contamination often meant catastrophic combustion. Many test launches ended with the missile exploding on or near the pad. Crews wore full protective suits, and even then suffered chemical burns and inhalation injuries. They were far from safe enough to launch expensive scientific payloads, let alone humans.

The decision was to simplify: Sergeant, Corporal’s successor, switched to solid propellant for field reliability. Solids were less efficient but much easier to store, transport, and launch. While liquid propellants gave high performance, they were unpredictable and dangerous, particularly with 1950s technology. If rockets were ever to carry people, that volatility had to be tamed. This realization drove new research into super-cooled (“cryogenic”) propellants, and the most-efficient-possible such fuel is liquid hydrogen, with liquid oxygen needed as an oxidizer. They were difficult to handle because of their extreme cold and low density, but they were clean-burning and, in principle, controllable. That control provided another advantage for upper stages of rockets which might need to shut down the burn, and reignite later.

However, the shift to cryogenic fuels introduced a new and largely unstudied hazard: sloshing. In early tests, engineers found that the movement of liquid hydrogen and oxygen inside their large, lightweight tanks could set up oscillations that interacted with the rocket’s guidance system — sometimes violently. The liquids didn’t stay neatly at the bottom; in microgravity, or changes in velocity, the liquids could surge, form bubbles, or expose feed lines to vapor. A brief gulp of gas instead of liquid could snuff an engine or send thrust in erratic pulses. Understanding and controlling that behavior was essential before such stages could be trusted to carry expensive payloads — or people. By the late 1950s, NASA needed someone to take on the challenge of figuring it all out. And here came Stofan, arriving in the right place at the right time, with the right training, and the curiosity and tenacity to take on the challenge.

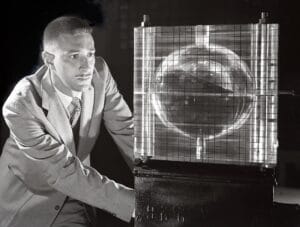

Stofan had to solve multiple problems brought on by sloshing, such as provide consistent flow, deal with changes in velocity, keep sloshing from altering the course of the spacecraft, figure out how much hydrogen and oxygen remained in the tanks after a burn, and draw the liquids back to the engines when it was time for reignition (but without bubbles). Stofan built clear tanks so he could see what the liquids inside did under varying conditions.

As he made progress, rocket designers made progress. In 1962, the development of the liquid-fueled Centaur upper stage was assigned to Lewis, and Stofan played a key role. He helped develop internal tank baffles to control propellant sloshing, gauges to measure fuel levels, and systems to ensure the right amounts of fuel and oxidizer were fed to the engines for the highest efficiency. The Centaur upper stage was used atop Atlas rockets by the Surveyor program, which sent JPL-built robotic spacecraft to the Moon in preparation for the Apollo missions.

By 1966, Stofan was the head of Lewis’s Propellant Systems Section — a critical position since liquid fuels would power the Saturn V rockets taking humans to the Moon. He was tasked to study booster pumps for Centaur stages, designed to increase fuel flow. After putting the engines through their paces in Lewis’s full-scale hot firing vacuum test facility, it was clear to Stofan that they were not needed, helping to simplify the design and lower the engines’ cost.

In 1969 he was promoted again, to the Assistant Project Manager for Improved Centaur. The task now: mate the Centaur to the more-powerful Titan rockets. In 1970 he was promoted again, to Manager of the Titan-Centaur Project Office, to oversee that job. He directed the design and engineering of the launch vehicles, and coordinated relations with Air Force, aerospace-industry teams, and mission planners. In these years, ten Atlas-Centaur and six Titan-Centaur missions were successfully flown, including launching Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11 probes to Jupiter and Saturn, two Viking missions to Mars, two Helios probes to the Sun, and two Voyager probes to Jupiter and the outer planets.

In 1978, Stofan became Deputy Associate Administrator for the Office of Space Science at NASA Headquarters, but three years later was lured back to the Lewis Research Center — to be its director. LRC was in danger of being shut down, but he revitalized the Center, got it back on track by removing an entire level of management to put employees in more control, and — once it was turned around — left it to a new director in 1986 so he could return to NASA headquarters to head the Space Station Office, directing the design of the Space Station Freedom (now “International Space Station” since few liked President Ronald Reagan’s name for the station). That is when I learned his name: I was hired by JPL in 1986 to work on documenting the Space Station’s systems for future mission designers. I never met or spoke with Stofan, but it’s almost certain that he read my weekly “Space Station Utilization Team Meeting Minutes”, which circulated as high as the White House (and are now in the permanent collection of the Internet Archive for future historians to study as they represented one of the few sources of the actual status of the program each week).

Stofan retired from NASA in 1988, and worked at Martin Marietta Astronautics as its vice president of Advanced Launch Systems and Technical Operations, then as president of Analex Corp., and then director of Electro-Optical Systems at Lockheed Missiles and Space Company. In 1999, Lewis Research Center was renamed the NASA John H. Glenn Research Center at Lewis Field — or, more colloquially, Glenn Research Center — in honor of the first American astronaut to orbit Earth. Once fully retired, Stofan lived in Steamboat Springs, Colorado, but still remained active as a Trustee of Hiram College. Andrew John Stofan died on October 26 in Fairfax, Va. He was 90, and still married to Barbara.