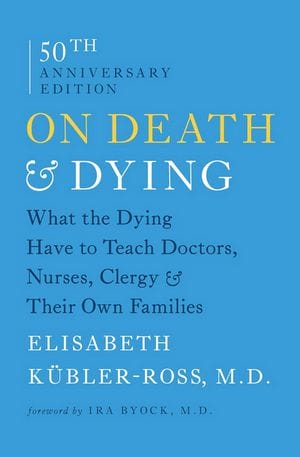

Born in Ottawa, Ont., Canada, Mount became a doctor, and was a urologic-cancer surgeon. In January 1973, his church’s leaders wanted to hold a discussion built around a book by psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross (Honorary Unsubscribe, 2004) — On Death and Dying * (1969) — which described the “five stages” of impending death that most patients who have the time go through: Denial, Anger, Bargaining, Depression, and Acceptance. The book, which broke a long taboo of studying death, was ground-breaking — and a best-seller. Being a doctor, Mount was asked by the church to organize the discussion, and thought maybe the evening would simply help church members better understand death.

“It didn’t occur to me that I didn’t have a clue about death and dying,” he said in an interview years later, even though he had survived cancer himself, and had therefore confronted his own mortality at just 24. “I thought, ‘I’m a doctor; I must know everything in the world about death and dying.’ But, of course, I knew absolutely nothing.” He brought in some of his doctor friends, and found the audience was very concerned about pain while dying, such as from cancer. One attendee suggested “someone” should study how death was handled in Montreal, as informed by the ideas in the book. Mount agreed to conduct the study, which effectively meant taking leave from his medical practice.

It’s important to know that there was no such thing as a hospice in Canada at the time. Indeed, there wasn’t even a single hospice in the United States, either — that didn’t come until Florence Wald (Honorary Unsubscribe, 2008), the dean of the Yale University School of Nursing, resigned that position to study with Dame Cicely Saunders, the founder of the world’s first hospice, in England, and then came back to Connecticut to open such a facility there in 1974. In Canada, Dr. Mount did what he promised, receiving a small grant from the faculty of medicine at McGill University, and recruiting two medical students to interview dying patients at Montreal’s Royal Victoria teaching hospital and compiling the results.

What they found shocked Mount: dying patients suffered terribly — and unnecessarily. “It became clear to me,” he said, “that to die at the Royal Vic was a catastrophe. And the Royal Vic, I would say, was one of the flagship academic hospitals in North America.” Doctors there, he said — and he was including himself — didn’t have any clue as to the “dimensions of our inadequacies. There was abysmal inadequacy in the control of pain and all other symptoms. And we’re not talking about stuff that’s difficult in most cases.” He extended his leave: the study revealed too large of a need to ignore.

Mount apparently didn’t know Florence Wald, but he learned of St. Christopher’s, Dr. Saunders’ hospice in England from Kübler-Ross’s book, and called to ask if he could come visit. She refused. “I know [your type],” she lectured on the phone. “You want to come over to London with your wife, see a few plays, have a quick run around the hospice, and then go back. Well, I won’t have it!” But, she continued, “I’ll tell you what: leave your wife at home, be prepared to stay for a week, roll your sleeves up and work hard, and I’ll have you.” He agreed, and traveled to London without his wife, arriving in September 1973.

Once Mount was taken to Saunders’ office, she sat him down. “What will you have for tea? Sherry or scotch? I am having scotch!” he remembered. “What do people call you?” he asked. “She stiffened, and said, ‘My friends call me Cicely. Others call me Dr. Saunders’.” As he was deciding which name he, as a fellow physician, should call her, she continued, “Steady, boy. I said my friends call me Cicely. You may call me Dr. Saunders.” He had sherry. “So, having been put in my place,” he continued, “I rolled up my sleeves and spent a wonderful week at St. Christopher’s. By the end of that week, I really understood what they were about, what they were doing and why they were doing it. I had met all the key players and taken part in the care. As I was going out the door, she said, ‘Oh, incidentally, you may call me Cicely’.” Their cordial relationship continued for decades, until she died in 2005, at 87 — from breast cancer, as a patient at St. Christopher’s.

“It was,” Dr. Mount said, “one of the most stimulating single weeks in my life. Once I saw St. Christopher’s, I saw there were solutions to that unnecessary suffering.” He had learned that hospice wasn’t simply about medical care: Saunders taught about “total pain” — the sum of the patients’ physical, emotional, social, and spiritual distress. “This was a major breakthrough,” Mount said. “In terms of the control of pain, one needed to consider each of those domains, and if you did, you could almost always get total pain control. Also important was her observation that the patient and family need to be considered together as the unit of care. These are Cicely’s enduring contributions; so much flows from them.”

But he also realized a stand-alone facility like St. Christopher’s was expensive to run, and decided to instead see if he could open a hospice ward at the Royal Vic. Even that was a tough sell, and it took awhile to get a two-year pilot program off the ground. Mount said that it was only his own status as a cancer surgeon that convinced the hospital to proceed: “It meant what I was suggesting was taken seriously in a way that it would never have been had I come out of psychiatry or psychology, even internal medicine.”

Mount shied away, however, from calling the new facility a “hospice” since that word in French was used to denote a nursing home for the aged. He decided to come up with his own term, coining “palliative care”. The new ward opened at the Royal Vic in January 1975 for inpatients, plus other patients were treated at their homes. Dr. Saunders actually didn’t like the term palliative care, “So I got particular pleasure when, a few years later, the Royal College of London and Edinburgh chose the term ‘Palliative Medicine’ as its new specialty,” Mount said. Even better, he was able to found the Division of Palliative Care at McGill University to teach more practitioners in the field.

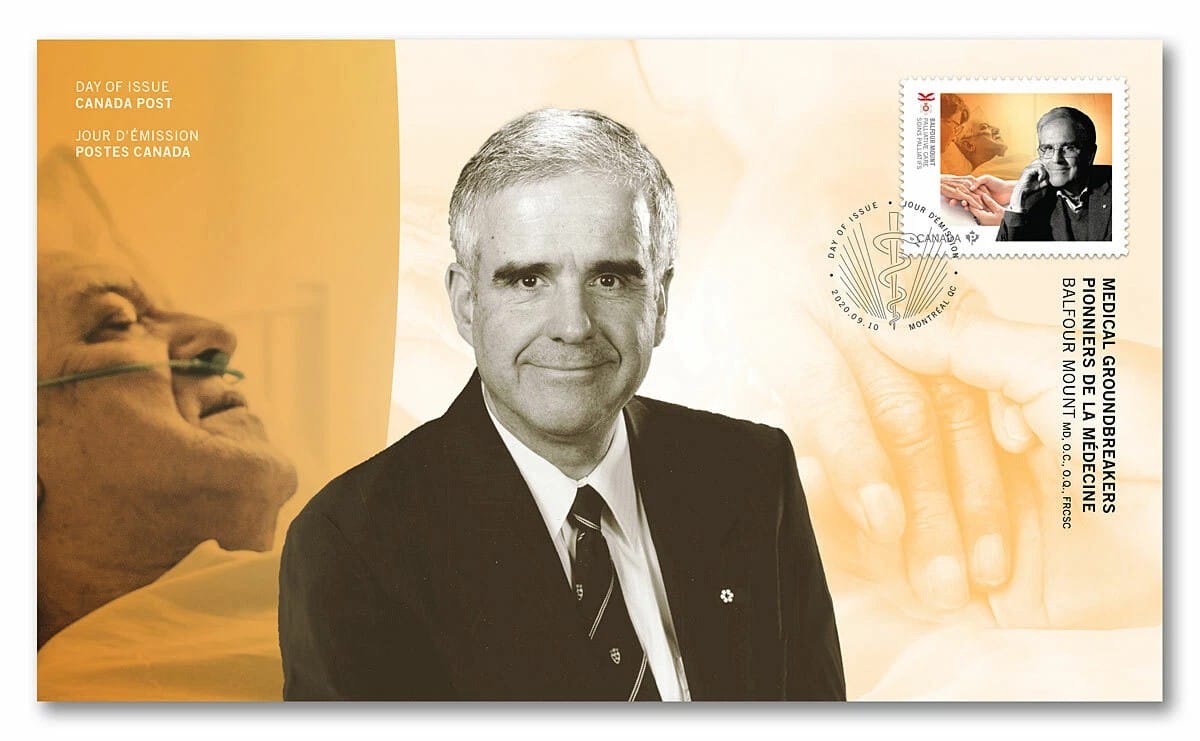

Dr. Mount was honored as a Member of the Order of Canada on December 23, 1985, one of the country’s highest civilian honors, recognizing outstanding achievement and service to the nation. The citation says, “Aware of the special medical and emotional needs of the critically ill and dying, which were not being met in the regular hospital environment, he founded the first Palliative Care Service at Montreal’s Royal Victoria Hospital. This unit, which has been copied nationally and internationally, has achieved its success through a combination of superb and compassionate medical care, pastoral services, and family therapy.”

There are several levels of the Order of Canada, and while rare, those who continue to exemplify the best of Canadian citizenship can be promoted to a higher level. Indeed, on October 30, 2003, Dr. Mount was made an Officer of the Order of Canada as he was “Considered the father of palliative care in North America, Balfour Mount is a model of compassion and humanity. Founder and former director of McGill University’s Palliative Care Division, he also created and directs the McGill Program in Integrated Whole Person Care. He has spearheaded research which helps practitioners deal with difficult ethical issues concerning people with advanced or life-threatening illness. In addition, he was instrumental in the creation and success of the highly regarded and largest international meeting on palliative care, held biannually in Montreal. His efforts have helped more people to receive professional care and to preserve their dignity in moments of ultimate suffering.”

Balfour Michael Morgan “Bal” Mount, OC, OQ, MD, LLD, FRCS(C), was diagnosed with esophageal cancer — in 2000. He survived that terminal diagnosis for 25 years, and didn’t even retire until February 2006. But indeed he died from that disease in the — yes — Balfour Mount Palliative Care Unit at Royal Victoria Hospital of the McGill University Health Centre, on September 25. He was 86.