Born in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, Jaguaribe worked as a clerk for Banco do Brasil, the oldest banking company in the country. He liked to make sketches on the side, and in 1952 offered some of his cartoons to a popular weekly magazine, and then also to a monthly. Over the next decade he saw growing fame, especially for his illustrations for the collections of Sergio Porto called FEBEAPÁ — an acronym for “The Festival of Nonsense that plagues our country”. He drew under an only slightly altered pen name, Jaguar.

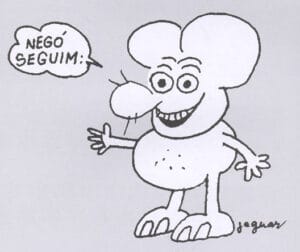

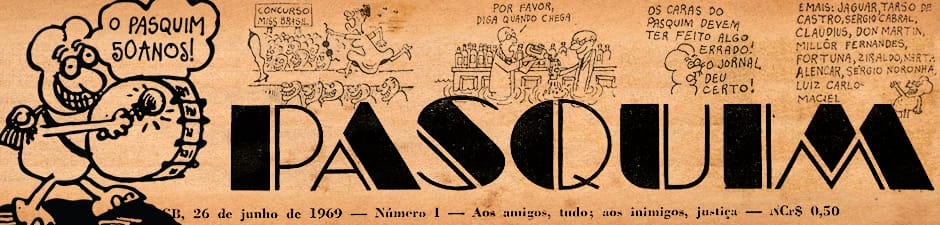

In 1969, with several other cartoonists and writers, Jaguar started the newspaper O Pasquim, first published on June 26. Named by Jaguar — after the Italian idea of a Pasquinade (satirical lampoon) — Jaguar whipped out a quick drawing of a mouse (though it was mostly referred to as a rat): “Sig” (a reference to Sigmund Freud, but also Jaguar’s retort to the cute money-maker, Mickey Mouse). Sig was the ever-present heckler, Jaguar said, gracing stories and interviews, typically saying “Negó Seguim:” Brazilian slang for “Here’s the deal:” — with the stories and cartoons following that everyone knew was the truth, not the dictator’s narrative.

The paper got a boost by having a scoop in its first issue: breaking news that Brazil’s dictatorial President Artur da Costa e Silva was being replaced by another military dictator, Gen. Emílio Garrastazu Médici. The first print run was 14,000 copies. It sold out in 2 days, and 14,000 more were printed. Within 5 months, circulation broke 100,000. It peaked at more than 200,000 copies per issue in the mid-1970s. In November, Médici cracked down on the newspaper, even as it was rising in popularity. “I was traveling, at my fishing house in Arraial do Cabo,” Jaguar remembered. “When I got back, they advised me: ‘Hide, Jaguar, everyone’s under arrest!’” He instead turned himself in; Jaguar and 10 colleagues were jailed for a little over two months, and the paper was required to submit its stories to censors before publication. Several staffers who escaped arrest had kept the paper going by constantly moving the newsroom, and telling readers that the main staff were suffering from a bad case of influenza. Other prominent writers and artists filled in with contributions, which strengthened Pasquim’s popularity even more.

Persistence beat the dictator: the publication was much more popular than he was. Médici didn’t exactly let it continue without harassment: the government did periodic raids, arrests, and even planted bombs twice. Jaguar simply reported on what was done when it published the issue.

But it couldn’t last forever: circulation peaked in the mid-1970s. Médici was succeeded in 1974, and President Ernesto Geisel started ramping down oppression despite hardliners wanting it to continue. Rio’s governor helped prop up the paper, and Jaguar was the only one of the founders remaining in the 1980s. O Pasquim finally stopped publication on November 11, 1991, after 1,072 issues — and that issue included still featured Sig, as drawn by Jaguar. It was “a rare case of a rat not leaving the ship,” he said; “he went down with it.” So did Jaguar: he was bankrupt, and took work editing a daily tabloid.

Did the downturn in his fortunes upset him? “If I were a type who cared, I would have myself killed long ago,” Jaguar said. In the 2000s, Jaguar was compensated by the government for the persecution of the early 1970s — R$1 million (about US$429,000 at the time). As “the Pasquim guy,” Jaguar had completely changed the tone of journalism in Brazil. In his words, he “took the jacket and tie off Brazilian journalism” by using a lighter interview style: a roundtable with — apparently literally — a bottle of whiskey on the table. The interview was typically printed as spoken, editing only slightly to improve flow. The result was widely imitated, though perhaps not including Sig, the mascot turned editorial voice. And he showed that government censors could not only be contained, but even mocked, not feared, by turning the censors into characters so readers could judge for themselves what was happening.

Brown University Library has hundreds of examples in its collection. “Initially imagined by the cartoonist Jaguar as the neighborhood newsletter of Ipanema, it soon became a national phenomenon. Famous for its role as the most successful oppositional tabloid to the military regime in Brazil, O Pasquim used humor to critique political coercion and the systematic violation of human rights by the Brazilian dictatorship.” And it did it right under the dictator’s twitchy nose.

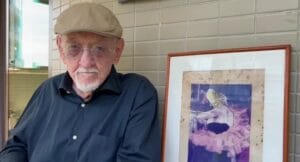

“Jaguar was a master, a teacher, a friend, an inspiration, a genius, one of the greatest cartoonists I’ve ever seen on the planet,” said cartoonist Renato Aroeira. “Tireless, he worked until the last minute, always absolutely critical, always fierce, always loved by generations and generations of cartoonists.” Indeed, his work is now considered so important, the Biblioteca Nacional do Brasil, or the Brazilian National Library, digitized the entirety of O Pasquim to make it available online: it’s used for teaching, and mined endlessly by researchers and historians.

Jaguar was hospitalized in Rio when pneumonia turned into kidney complications. Sérgio de Magalhães Gomes “Jaguar” Jaguaribe died there on August 24, at 93.