Born in Michigan and raised in Stamford, Conn., Jarvik came from a medical family. His uncle, Murray Jarvik, was a pharmacologist who co-invented the nicotine patch. His brother, Jonathan Jarvik, was a biological-sciences professor at Carnegie Mellon University. Robert also had an interest in mechanics, and while getting his bachelor’s degree from Syracuse University, Jarvik’s father, a family doctor, had a heart problem, and went to Texas for surgery from Dr. Michael DeBakey which saved his life. That made a big impression on Robert, who went on to earn his Master’s in medical engineering from New York University — and then he went to medical school, at the University of Utah.

Just two years into that program he was hired by Willem Johan Kolff, who invented the first artificial kidney, which led to the dialysis machine, and had successfully built the first heart-lung machine at the Cleveland Clinic to keep patients alive during heart surgeries. At the University of Utah, Kolff headed the Artificial Heart Research Lab. Jarvik graduated with his M.D. in 1976 but, wanting to devote himself to research and medical devices, never went through an internship or residency, and never pursued a license for clinical practice. Instead, he received the assignment from Dr. Kolff to be the principal designer of a new artificial heart.

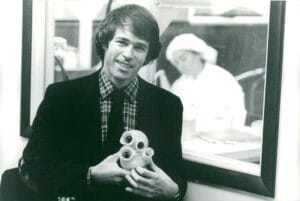

In 1976, his Jarvik 5 model heart kept a calf, Abebe, alive for 184 days, more than doubling the record set just a year earlier with a heart of Kolff’s design. There were other artificial heart programs too. In 1969, the Texas Heart Institute did the first implant of an artificial heart into a human; it sustained him for 64 hours until a donated human heart became available. That patient died of an infection 32 hours after that donated heart was implanted.

By 1982, Jarvik’s 7th model artificial heart was ready to be tried on a human. Experimental? Sure: but with a shortage of donated real hearts, it was a choice of artificial or die for many, and on December 1, 1982, Dr. William DeVries implanted the Jarvik 7 into retired dentist Barney Clark, who was dying from congestive heart failure. The heart needed to be powered by a 400-pound external box, and Clark suffered multiple complications; he was torn between wanting to die — he had only expected to live for a few days since it was so new — and wanting to help further research to help future patients. Clark died from multiple organ failure on March 23 after 112 days with his mechanical Jarvik heart. The case raised ethical debates: had doctors crossed the line in “playing god”?

The University of Utah insisted that Drs. Kolff and Jarvik, and other members of the team, not do press releases or give interviews; all news was to be dripped out by the University Press Office, he said years later. “The news about Barney Clark stunned the doctors by making headlines around the world”, he said. “Enormous public interest developed, and hundreds of reporters converged on Salt Lake City to cover the story, and the University began to give them daily briefings, which were completely uncensored. All medically significant events in the post-operative course were reported” — not just the successes, but the setbacks. “The sheer volume of information and the extraordinary degree of transparency created a sort of medical experiment in a fishbowl,” he said, leading to unrealistic expectations in families with a member suffering from severe heart disease.

The Jarvik 7 was used on another patient in late 1984; despite being similarly tethered to the support machine, Bill Schroeder was able to leave the hospital to stay in a nearby apartment, and even was able to travel to his hometown in Indiana, where he was given a parade. He lived 620 days. Three other patients received Jarvik 7s with varying levels of success. The ethical questions died down: people actually grew tired of “What, another artificial heart implant?” and lost interest. But several more Jarvik 7s were implanted as a bridge to keep the patient alive long enough to get a transplant. One patient lived 5 years, another 11 years, and the last 14 years. Yet the press simply assumed that Jarvik had given up on artificial hearts, or that they had been banned by the FDA. Jarvik had started a company, Symbion, to make his hearts, but was forced out in a hostile takeover. By the time that company failed in 1990, 198 patients had been treated with Jarvik 7 hearts.

Today, thanks to organ donation programs it’s much more likely for heart patients who need a complete new heart to receive a donated heart. Those not quite to that level of need are helped well by a Ventricular Assist Device, which works with the patient’s heart to pump blood more effectively. Dr. Jarvik embraced VADs fully: “If you had a failing arm or leg, would you rather have the best-possible artificial limb, or a device that allowed you to keep your own arm or leg?” In 1988, he started work on his own VAD; a smaller one for “kids, infants, and neonates” is currently under clinical study. VADs are a direct descendent of experiments with artificial hearts; the Jarvik program was absolutely a resounding success.

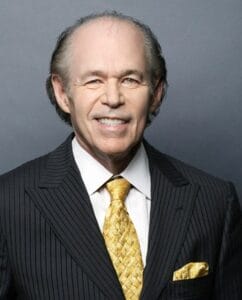

Dr. Jarvik’s first marriage ended in divorce in 1985. In 1987 he married Marilyn vos Savant, best known as having the highest IQ score ever recorded (Stanford–Binet, 228). Robert Koffler Jarvik died at their home in Manhattan, NYC, on May 26, from Parkinson’s disease. He was 79.