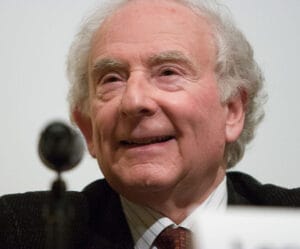

Born in the Bronx of New York City to Irving and Anna Kupchik, at age 7 his mother died, and Leon went to foster care with his younger sister. Irving changed his name to Cooper, remarried, and was able to bring his children home, with a new name. Leon had an interest in science, and attended the Bronx High School of Science, graduating in 1947. In high school, he stayed late after school to do experiments. One was to study the new miracle drug, penicillin. “It was just an idea I had,” he said years later: he was interested in antibiotic resistance, and how it developed. Not many were thinking about that in 1947, but he did, and grew colonies of penicillin-resistant bacteria by subjecting them to weakened solutions of penicillin. Cooper wrote up on his results and entered his report in the 1947 Westinghouse Science Talent Search. He was named a finalist, which came with a cash prize. He decided to go to Columbia University.

That forced a decision: should he study biology, or the other subject that interested him? “I just wanted to work on deep and important problems,” he said. “It was a hard choice. I remember my thinking at the time was that I could always learn biology, but if I didn’t really study physics, I’d never understand it.” He chose physics because “there is no other way that I can know about everything,” and earned his bachelor’s degree in the subject at Columbia in 1951, his Master’s in 1953, and his Ph.D in 1954. He spent a year at the Institute for Advanced Study, and taught at the University of Illinois and Ohio State University, and in 1958 joined Brown University in Providence, R.I.

Meanwhile, University of Illinois physicist John Bardeen, who had won the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1956 (with William Shockley and Walter Brattain for the invention of the transistor), was studying superconductivity, which was discovered in 1911 but no one knew how it worked. Bardeen was trying to crack the problem, and brought in one of his grad students, J. Robert Schrieffer, to help. But Schrieffer needed help. Bardeen knew of Cooper from the Institute for Advanced Study, and asked him to take a piece of the puzzle too. Cooper had never heard of it, but agreed.

Cooper said later that had he known that many of the top physicists had tried to explain superconductivity, including Albert Einstein, Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg, Wolfgang Pauli, and Richard Feynman, and all failed, he wouldn’t have agreed to try. But it only took Cooper a year to suggest a solution, which was published in 1956. It still needed to be proven, and that’s where Schrieffer came in: he figured out the math. It took months for the three physicists to patch it all together, and in July 1957, the “BCS Theory” (for Bardeen, Cooper, and Schrieffer) was published as “Theory of Superconductivity” in Physical Review. Subsequent experiments confirmed the BCS Theory, and the trio won the 1972 Nobel Prize for Physics. Dr. Bardeen remains the only person to have won the Prize in Physics twice.

A Nobel Prize often gives a professor license to put his attention to where he wants, and for Cooper that was …biology! More specifically, he wanted to learn how humans learn — how memory works. In 1973 he founded the Institute for Brain and Neural Systems at Brown, and went to work. This time it was Cooper who pulled together a team with two grad students, Elie Bienenstock and Paul Munro, and in January 1982, in the Journal of Neuroscience, the BCM Theory, based on synaptic plasticity, was published. “The [BCM] theory made assumptions about how neurons are modified, and those assumptions were testable,” said Dr. Mark F. Bear, a professor of neuroscience at MIT who had studied under Cooper. “Those assumptions were also correct.” BCM, he says, is “foundational” in the field of neuroscience, even explaining how humans learn to see. Dr. Cooper died at his home in Providence, R.I., on October 23. He was 94.