Born in Nashville, Tenn., to a father (James Geddes Stahlman) who was both a newspaper publisher and a trustee of Vanderbilt University, education was part of Stahlman’s life. At around 11 years old she was given a microscope, and decided to be a doctor. Naturally, Millie went to Vanderbilt for her bachelor’s degree, received in 1943, and earned her Medical Doctorate at Vanderbilt’s School of Medicine in 1946. She interned in pediatrics and cardiology, and received a fellowship at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, Sweden, where she studied pediatric cardiology. It was there, she said, that she became “hooked” on the care of newborn infants. She became an instructor in Pediatrics at Vanderbilt in 1951.

In 1954, Dr. Stahlman received a small grant from the National Institutes of Health to study “hyaline membrane disease” — what’s now called respiratory distress syndrome. Through the grant, a lab was added adjacent to the Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s nursery, and Dr. Stahlman obtained a prototype of a respirator. On October 31, 1961, shortly after Stahlman became the director of Vanderbilt’s Division of Neonatology, a baby girl at VUMC was born prematurely with underdeveloped lungs. Dr. Stahlman used the respirator to help her breathe. “For the first time in the history of medicine,” VUMC said, “a premature baby who would not have survived was saved by the use of a respirator.” Out of that effort, Dr. Stahlman helped Vanderbilt create the world’s first NICU — Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. That first baby saved, Martha Lott, grew up to become a nurse. The place she chose to work: Vanderbilt’s NICU. “I think they assumed I would have issues,” Ms Lott said, referring to the experimental treatments she received. She’s fine. Still, “It’s amazing how much technology has changed in the last 60 years.” By 1965, using that respirator — a tiny negative-pressure device based on the iron lung for polio patients — had saved 11 of 26 premature babies brought to Vanderbilt. In the several years after that, positive-pressure devices improved enough to fully replace them, and helped increase the odds of survival.

One question Stahlman tackled in her research was why there are now so many premature births in the U.S. “Prematurity has become largely a social rather than a medical disease in the United States,” she concluded in 2005, publishing her findings in the Journal of Perinatology. “The rapid rise of hospitals for profit with shareholders’ interests dominating the interests of our patients was followed by neonatology for profit, and profitable it has been.”

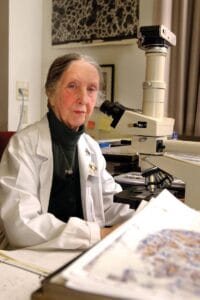

Dr. Linda Mayes, chair of the Yale Child Study Center who trained under Dr. Stahlman, said “Millie was one of the first to push the limits of viability of premature infants in a careful and scientific way. She was a physician-scientist long before that phrase was popular.” Her standards were high, and she demanded the same out of the residents she trained. They remember that during “Millie Rounds,” they were expected to know everything about the babies they cared for, including conditions they’d be released to once they got to go home. “Her rigor was shocking to the mostly male staff, especially coming from a woman who was barely five feet tall and 90 pounds,” said Dr. Elizabeth Perkett, a now-retired professor of pediatric pulmonology the University of New Mexico — and before that, at Vanderbilt University. Dr. Mildred Thornton Stahlman apparently never fully retired — nor married or had children of her own. She died at her home in Brentwood, Tenn., on June 29, at 101.