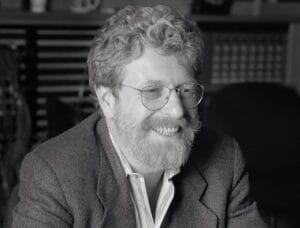

A musician growing up, Cuscuna played jazz — specifically on drums, sax, and flute, but his end goal was bigger: he wanted his own record label. To get there he set his path on learning, hosting a jazz show on WXPN radio, a public station at the University of Pennsylvania, in the 1960s. He was good enough that he moved to WWMR, and then WABC-FM in New York City. Along the way he wrote for music magazines, including Jazz & Pop, Down Beat, and Rolling Stone, and produced concerts for bands that didn’t have managers.

But “at the end of 1971, free form radio was gone and all the FM stations had formats and playlists. So I quit radio: it wasn’t fun or creative anymore,” he said in 2008. Then he got a lucky break: a friend at Atlantic Records said he needed an assistant, so he hired on as a producer, working on records for Dave Brubeck, Oscar Brown Jr., Bonnie Raitt, and convinced Atlantic to sign the Art Ensemble Of Chicago. By the early 80s, things slowed down and he was laid off, along with his friend Charlie Lourie. “We made a proposal to EMI to relaunch Blue Note, but they were not yet ready to add a jazz division. Part of the proposal was box sets, specifically ‘The Complete Blue Note Recordings Of Thelonious Monk’. At some point, I realized that if we made these limited editions and sold them via direct mail only, these box sets could be a business in and of itself. So we started Mosaic Records” in 1982, to do just that.

He and Lourie would license the set recordings from record companies where the music was scattered across various albums, or maybe out of print, or sometimes never even published, and produce a complete set under license, usually specified to sell 5,000 copies — which limitation would sometimes create a significant demand. The break-even point was usually around 1,000 copies, and after a few years of struggle, the company started doing pretty well. Well enough that it still exists today, with more than 200 titles produced and, with no ability to make more copies, are considered collectors’ items. Mosaic is “the most distinctive reissue label in jazz,” the New York Times says. Some of the “complete sets” were absolutely extensive: the complete masters of Milt Gabler’s Commodore Records was such a big collection, it was issued in three volumes — totaling 66 Long-Play records.

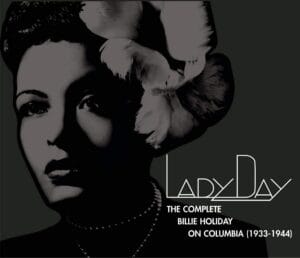

Cuscuna was still longing for a revival of Blue Note Records, which had gone defunct. In 1979, EMI had purchased United Artists Records, which owned Liberty Records, which had bought out Blue Note in 1965. The label was originally founded in 1939 and became one of the most prolific, influential, and respected jazz labels of the mid-20th century, helping to establish and develop hard bop, post-bop, and avant-garde jazz. It had an extensive catalog featuring a wide variety of artists, and EMI not only revived it, it brought in Cuscuna as a freelance advisor and reissue producer. He helped re-issue carefully crafted sets, and wrote meticulous liner notes. Sometimes Blue Note would release the sets under the Mosaic label. Cuscuna won three Grammy Awards: Best Historical Album for “Nat King Cole, The Complete Capitol Trio Recordings” (1993), Best Album Notes for “Miles Davis, Miles Davis Quintet, 1965–68: The Complete Columbia Studio Recordings” (1998, with Bob Belden and Todd Coolman), and Best Historical Album for “Billie Holiday, Lady Day: The Complete Billie Holiday on Columbia (1933–1944)” (2002, with Michael Brooks).

Blue Note expanded as other record companies placed their own jazz catalogs with the company. “Cuscuna may have been the most prolific archival record producer in history,” the New York Times said. “Starting in an era when midcentury jazz experienced a resurgence of interest, his name showed up in the fine print on over 2,600 albums” — as a producer, researcher, consultant, or author of the albums’ liner notes. What drove that passion? “Finding something that’s never been heard before and causing it to come out, for me, was always an incredibly gratifying thing,” Cuscuna said. “Even if you put something out and it only sells a thousand copies and gets deleted in two years… once you put it out, it exists. Once it’s out in the world, it’s out in the world. That can get copied, it can get analyzed, it can get critiqued. But if it’s just sitting on a shelf, it only exists in a theoretical way. It does not exist.”

“Plainly stated, Blue Note Records would not exist as it does today without the passion and dedication of Michael Cuscuna,” the company said announcing his death. Cuscuna died on April 20 at his home in Stamford, Conn., from esophageal cancer. He was 75.