While he could easily pass for white with his light skin and green eyes, Harris was proud of his Black heritage, and wouldn’t allow anyone to mistake him for white. In college, he was rejected by the military’s ROTC program because he was Black. He kept applying anyway, and was finally accepted, and rose to Cadet Colonel. He joined the U.S. Air Force because he wanted to fly. He did: B-47 and B-52 bombers. But he got so tired of housing discrimination — even though he was an officer — he gave up on the military after six years and hoped to fly airliners, emboldened by the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. He was honorably discharged as a captain.

On his applications to the airlines, Harris still wrote on the applications, “I’m married, I have two children and I’m black.” Some airlines didn’t even reply. All the others rejected him, except one called him in for an interview: American Airlines, headquartered in Texas. Harris started the interview by telling the Chief Pilot he was Black. “This is American Airlines and we don’t care if you’re black, white or chartreuse,” the Chief replied. “We only want to know, can you fly the plane?” He certainly could, so they hired him. It was December 3, 1964, two days after leaving the Air Force, and Harris became the first Black pilot hired by any major U.S. airline. A bit less than three years later, he was promoted to Captain, another first in the U.S.

He wasn’t given piddly regional assignments. Harris piloted a number of different aircraft, including the Boeing 747, Boeing 727, Boeing 767, the Airbus A300, the Douglas DC-6, the Douglas DC-7, the Lockheed L-188 Electra, the BAC One-Eleven, and the McDonnell Douglas MD-11, the latter American Airlines’ largest aircraft at the time of his retirement, in 1994 after 30 years. “I would have done it another 30 years had I not grown old,” Harris said. “It’s the greatest job in the world. I flew and flew and flew and was ready to fly more in my life.”

Once established, Harris worked to mentor other people — particularly Black men and women — who wanted to fly. He proudly posed for a photo of another American Airlines first: the first all-Black flight deck crew, dubbed the “Soul Patrol”: Harris, First Officer Jim Greene, and Flight Engineer Sam Samuels. “Reaching back and helping others to succeed,” Harris said, “that’s what I’d like for my legacy to be.” American Airlines is proud to have led the industry. “Capt. Harris opened the doors and inspired countless Black pilots to pursue their dreams to fly,” CEO Robert Isom said in a statement. “We will honor his legacy by ensuring we continue to create access and opportunities for careers in aviation for those who otherwise might not know it’s possible.”

In 1967, Harris heard civil rights leader and National Urban League executive director Whitney Young was on his plane. Harris stepped out of the cockpit to introduce himself to Young, and thanked him for helping African Americans get jobs in various fields, including aviation. Four years later, Young drowned at a conference in Africa. Young’s wife, Margaret, asked American Airlines to locate the pilot Young met years earlier. She wanted him to fly her husband’s remains back to the United States. American Airlines offered an all-African-American flight and cabin crew, but Margaret refused. “That’s not the way of the Urban League. It should be black and white together.” American honored her wishes, with Harris piloting.

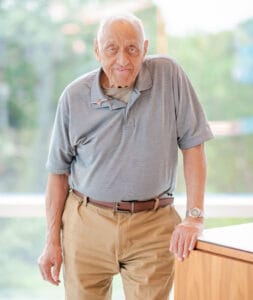

“He was standing on the shoulders of the Tuskegee Airmen who was around in World War II,” said Paul Pierre, a Black American Airlines pilot who has been with the airline for 25 years. “I am standing on his shoulders because of what he did.” The airline, he said, “recognized even back then, that if we’re going to call ourselves American Airlines we need to represent the values that America stands for.” But Harris said it should have happened well before he came along. “The reality is that there were 500 pilots — Tuskegee Airmen — who were qualified for airline jobs when they left the service. None of them received an opportunity to sit in a cockpit. There is no way I should be the first; it should’ve happened long before 1964.” David Ellsworth Harris died in a hospice in Marietta, Ga., on March 8. He was 89.

Cool story!

I always wondered why I particularly liked American Airlines, and not just because of their exemplarily service both in the terminal and in the air. A few years ago, a Black counter attendant efficiently moved heaven and earth to get me home from being stranded in a blizzard in Cincinnati without breaking a sweat and would barely accept my thanks or tip because “it was her job.” She got a letter of praise to the home office in Dallas for her service, above and beyond the call of duty (ABCD). Shame on the other airlines in the past dark days of overt racial prejudice. I’m glad American was most concerned that he could fly the plane and not the color of his skin.

Shame on America for the past and present dark days of racial prejudice, much of which is no longer quite so overt, and which it could be argued is worse.

—

We (USA and South Africa) have quite the ugly history. It seems the USA is doing worse on sliding back, as well as trying to cover up the ugly parts of our history, and that is to our shame. -rc

I disagree that the US is backsliding. The vocal minority (Both black and white) are getting the attention because it’s “news”. But the vast majority of us are living “cheek to jowl” with all other races, Black, Caucasian, Asian, Middle Eastern, etc. and just don’t think about it until the jerks get loud. We are so far beyond where we were when Captain Harris was breaking ground and it is a great thing. God bless the USA and our ability to admit our mistakes, learn, and move on.

And it took another nine years before Bonnie Tiburzi became the first female commercial airline pilot in 1973. Coincidentally, also for American Airlines.

—

Maybe not coincidentally. Seems they had more open minds in the day. -rc

And NASA launched Americans into space for 28 years before they finally chose Fred Gregory to command the 32nd Space Shuttle flight in 1989. And then another ten years to choose Eileen Collins to command a flight in 1999, the 95th Shuttle launch. I had the good fortune to meet them both, and witness Ms Collin’s launch. I am hoping that we are catching up to the rest of the world. Maybe one of these days we will figure out how to choose a woman president. Since more than 50 percent of us are not female, it makes sense to me.

As a retired American Airlines pilot, I have worked, trained, and flown with thousands of AA pilots over the years. White, Black, Male, Female, etc. — it didn’t matter. We were all Professional Pilots who could fly the plane and take care of the passengers. That’s what matters in the cockpit.

—

Thinking. What a concept. -rc

For some years I flew regularly from a regional airport where the standard plane was a 30-passenger turboprop. One flight had the first non-White crew I’d seen: a young, Black female pilot; a male first officer apparently of Middle Eastern origin, and a Black female flight attendant. I remember thinking that was pretty cool, but also feeling a little guilty that it was something still unusual enough to draw attention.