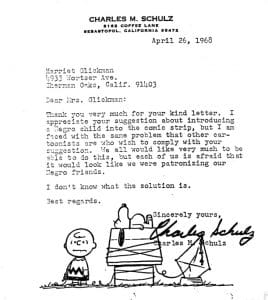

After Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in April 1968, Glickman, a mother of three and a schoolteacher in a suburb of Los Angeles, wrote a letter to the author of the biggest-circulation cartoon strip in newspapers of the day, Peanuts’ Charles Schulz, suggesting that it was time for “the introduction of Negro children into the group of Schulz characters.” Also, she added, “Let them be as adorable as the others.” Schulz quickly wrote back to say a number of cartoonists had been considering just that, “but each of us is afraid that it would look like we were patronizing our Negro friends.” Glickman got two black friends to write letters, which she forwarded, including from Los Angeles City Councilman Tom Bradley, who would later be elected mayor. Convinced, Schulz designed a character, and “Franklin” debuted in July.

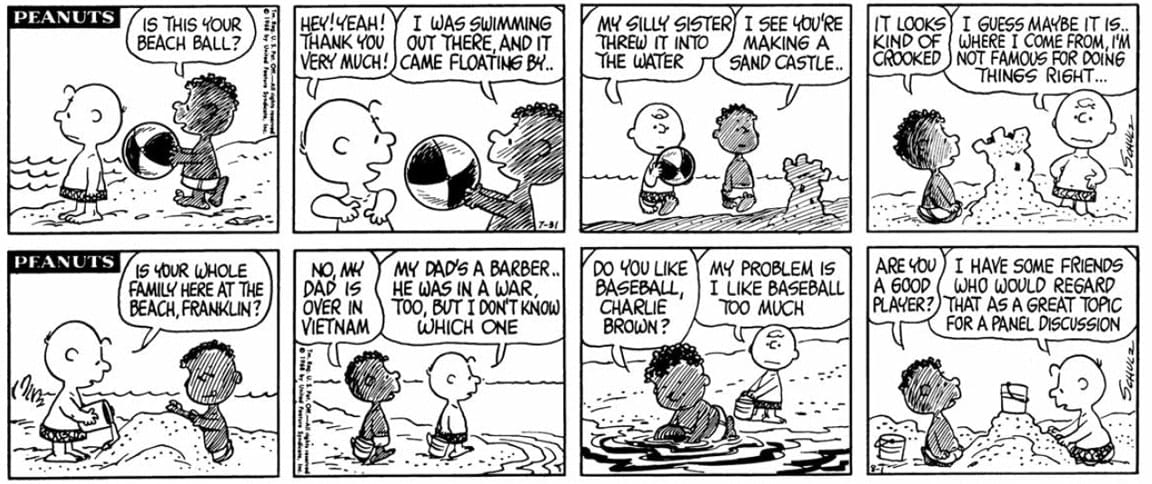

It was a cautious debut (below). Of the first five strips with the new character, “Franklin is in ten panels and Sally is in eight, but never is Franklin in the same panel as the white girl,” notes Nat Gertler, the author of two books about Schulz. “Franklin was never granted any of the sort of usual quirks that define a Peanuts character.” But still, he was there, and recurred through 1999, a year before Schulz died at 77. “What inspired me was everything up to that moment that the African-American community had gone through,” Glickman said years later. “This was the worst of the civil rights period and I felt that sense of ‘Is there anything I can do?’” Having Schulz respond to her suggestion “was thrilling,” she said. “Franklin has become like a member of our family. He’s a fourth child to me.” She collected whatever “Franklin” merchandise she could find, and was widely recognized as someone who just decided to “do something” to make the cartoon world resemble the real world just a little bit better. Glickman died March 27, at 93.