An officer in the USSR’s air force, in the 1970s Petrov was assigned to their “early warning” system, and had risen to the rank of Lt. Colonel. In September, 1983, the Cold War with the west was hitting a fever pitch. That spring, U.S. President Ronald Reagan had declared the USSR an “Evil Empire” and announced the “Strategic Defense Initiative” — a missile defense system which became known as “Star Wars” — that had been outlined by the U.S. Citizens’ Advisory Council on National Space Policy, chaired by Jerry Pournelle (see Honorary Unsubscribe, last week), based in large part on the military textbook The Strategy of Technology (lead author: Jerry Pournelle). To make matters worse, on September 1, the Soviets had shot down a plane that had strayed into its airspace — a civilian jetliner, Korean Air Lines Flight 007, with 269 passengers and crew aboard, including a U.S. congressman; all were killed.

In the middle of that tense environment, on September 26, 1983, alarms went off at Serpukhov-15, the Soviet’s secret command center outside Moscow where Col. Petrov was in command. The alert: their early warning satellites showed that the United States had launched an Intercontinental Ballistic Missile toward Russia. Then another, and another, until it showed five missiles were on their way. As the commander in charge of about 200 people, all eyes turned toward Petrov, then 44 years old. “For 15 seconds, we were in a state of shock,” Petrov remembered later. “We needed to understand, ‘What’s next?’”

Ground-based radar was not showing incoming missiles, but that was expected: they wouldn’t show that until the missiles got much closer. Should he pass the warning up his chain of command, who would call the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Yuri Andropov, for authority to launch a counterstrike? Andropov, the former head of the KGB, had been warning about an attack by the Americans, and now their own systems were showing it had started. There was very limited time to react, but Petrov decided to take that time and think, as “There was no rule about how long we were allowed to think before we reported a strike,” Petrov said in a 2013 interview. He figured it was “50-50” — an equal chance that the warning was real, and that the warning was some sort of malfunction. His gut said malfunction. Even though status readouts on his systems changed from “launch” to “missile strike,” he went with his gut and made his decision: “When people start a war, they don’t start it with only five missiles,” he told the Washington Post in a 1999 interview; he declared the warning a malfunction, and that decision was communicated up the line, chasing behind automatic reports that were apparently issued because there was more than one missile detected.

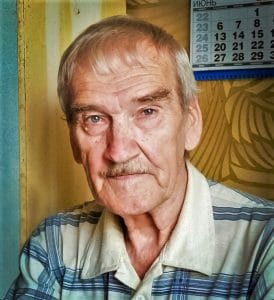

Indeed the alert was in error: system software had caught glints of sunlight on the top of clouds in North Dakota, and misinterpreted the data. The Soviets issued Petrov a reprimand: why hadn’t he recorded more details in the station’s War Diary? “Because I had a phone in one hand and the intercom in the other, and I don’t have a third hand,” he replied. Others were a bit more grateful that Petrov aborted the end of the world, as the military doctrine of the time, “Mutual Assured Destruction” (or “MAD”) dictated: that doctrine asserted that the only sure deterrent for nuclear war was the knowledge that if one side initiated a missile attack, the other side would immediately respond in kind, destroying both sides. Petrov took early retirement the next year, and — the whole event shrouded in secrecy — lived in anonymity …and suffered a nervous breakdown. His role in averting the end of civilization came to light when the retired commander of the USSR’s missile defense system, Gen. Yuriy V. Votintsev, published his memoirs in 1998. In 2006, Petrov was honored by the United Nations. In 2013, Petrov was awarded the Dresden Peace Prize. He died May 19, 2017, at 77, but due to his keeping such a low profile (“I was just at the right place at the right time,” he says in a documentary about that night), and the desire of Russia to downplay the incident, news of his death didn’t make it to the west until mid-September.