A writer, in 1961, Michaels noticed a magazine addressed to her roommate showed her name as “Ms. Mari Hamilton” — not Miss or Mrs., as was almost universal at the time. Michaels thought it was a typo, and pointed it out to her roommate, Mari. No, Mari replied, that was no typo: it was how that radical magazine addressed women; the honorific goes back to at least 1901, when it was promoted by the Springfield Republican newspaper in Massachusetts (to little avail). Michaels was thunderstruck. “I didn’t want to be owned. I didn’t belong to my father and I didn’t want to belong to my husband,” she said later. “I had not seen very many marriages I’d want to emulate — the whole idea came to me in a couple of hours. Tops.” Indeed, she decided, “‘Ms.’ is me!” She worked to popularize the form of address, but even the feminist movement rejected the term. The title didn’t really take off until she was interviewed on WBAI Radio in New York City in 1969, and she pushed for it there.

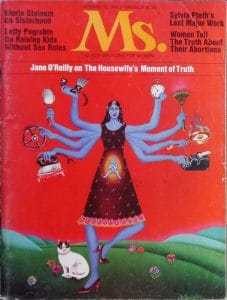

The interview was brought to the attention of feminist Gloria Steinem, who was working to develop a magazine created by and for women. Ms. — the resulting magazine — debuted in 1971. In its first issue, Ms. editorialized that it adopted the title “as a standard form of address by women who want to be recognized as individuals, rather than being identified by their relationship with a man.” From there, it spread like wildfire. In 1986, the New York Times admitted that they hadn’t used the term in news reports “because of the belief that it had not passed sufficiently into the language to be accepted as common usage.” NYT stockholder and feminist Paula Kassell challenged publisher Arthur Sulzberger to “convene a debate with language experts to reach a ‘rational decision’” on the term. He accepted the challenge, but didn’t wait for the debate: on June 20, 1986, the paper announced on Page 1 it would start using the term in its columns. By then, “Ms.” had been listed in the American Heritage school dictionary for 14 years, and its main dictionary for 11 years. Michaels, meanwhile, went on to write, edit, record oral history interviews of civil rights leaders, drive a New York City taxi, and operate a Japanese restaurant with her husband. Ms. Michaels died in New York on June 22, from leukemia. She was 78.